In this episode of The Bible for Normal People Podcast, Pete and Jared talk with Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Brettler about some of the themes of their new book, The Bible With and Without Jesus as they explore the following questions:

- How does the Bible function differently for Jews and Christians?

- What is fundamental in the Jewish reading of the Bible?

- How do we know how people interpreted the Bible in ancient times?

- How does scripture communicate to us?

- What are some of the problems language causes in interpreting the Bible?

- How does punctuation affect interpretation of biblical Hebrew?

- Why is recognizing how we want scripture to function for us important to be aware of?

- Would the Bible have survived all this time if its meaning was crystal clear?

- What is a revelatory interpretation?

- How does a writing’s meaning change when interpreted prophetically?

- Does Jesus or John the Baptist appear in the Dead Sea Scrolls?

- What is a pesher and how does it work?

Tweetables

Pithy, shareable, less-than-280-character statements from Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Brettler you can share.

- “We’re not reading the same Bible at all and that actually is pretty good, because then we don’t have to wrestle over I got it right and you got it wrong.” — Amy-Jill Levine

- “We’re not always even reading the same book.” — Marc Brettler

- “When we start talking with each other, Jews and Christians, about what strikes us in the Bible, we frequently miss because what the Jew finds important, the Christian may find irrelevant or not know very well and vice versa.” — Amy-Jill Levine

- “The vocabulary of biblical Hebrew is tiny when compared to the vocabulary of English. So, therefore, many words naturally have homonyms because you have fewer number of words but have to talk about the same human reality.” — Marc Brettler

- “When our neighbors give us their perspective on the text, we get to know our text better as well.” — Amy-Jill Levine

- “Any literary text cannot speak for itself and requires interpretation.” — Marc Brettler

- “Interpretation if part of the human condition.” — Amy-Jill Levine

- “Scriptural texts, by their nature, require flexibility so that they’re able to adapt to different times and places.” — Marc Brettler

- “The text shows us that it’s necessarily interpreted right from the get-go and even something that might be really clear, like an eye for an eye, isn’t.” — Amy-Jill Levine

Mentioned in This Episode

- Book: The Bible With and Without Jesus

- Class: Beyond the Prince of Egypt

- Patreon: The Bible for Normal People

0:00

Pete: You’re listening to The Bible for Normal People, the only God ordained podcast on the internet. I’m Pete Enns.

Jared: And I’m Jared Byas.

[Jaunty intro music plays, then fades as speaker begins]Jared: Welcome, everyone, to this episode of The Bible for Normal People. Before we jump in, just want to mention that we have a class. If you haven’t heard the last few weeks, we have the book Exodus for Normal People out now. We thought it would be great to do a one-night class as well on Exodus, you know, because we just can’t get our fill of Exodus. So, February 25th, 8:30 – 10:00 PM ET, it’s called “Beyond the Prince of Egypt: How to Read the Book of Exodus Like an Adult.” Pete, you want to give a word about what you’ll be doing?

Pete: Yeah, way beyond the Prince of Egypt. So, yeah, the book of Exodus is intriguing, challenging, complicated, and there are just a lot of moving parts. So, we were going to talk about that in an hour with some Q & A afterwards and just sort of highlights about what’s going on in this book and what it means to read this book with adult eyes and not just sort of as a story we know as children.

Jared: Yup! So, go to https://peteenns.com/course/prince/ to learn more. It’s pay what you can, so we don’t want to turn anyone away, again, for a lack of funds. Pay what you can for this one-night class, February 25th, 8:30 – 10PM ET. See ya there.

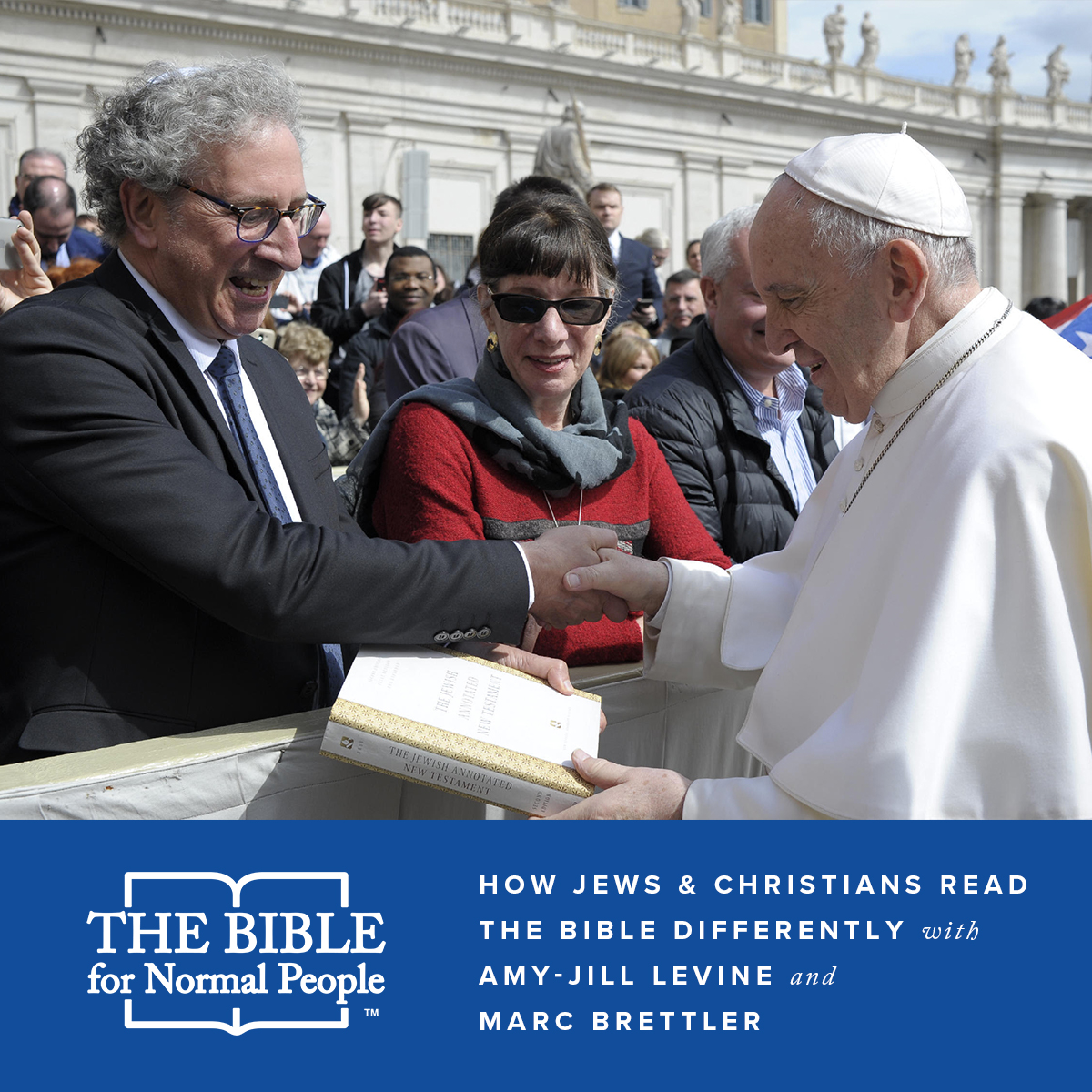

Pete: Now, for our episode today, the title is “How Jews and Christians Read the Bible Differently,” and we had two wonderful guests that both, Jared, are back. They’ve been here before but AJ Levine, who is a Professor of New Testament at Vanderbilt University and Marc Brettler, who is a Professor of Judaic Studies at Duke University. And they came out with a new book, and the title is The Bible With and Without Jesus: How Jews and Christians read the Same Stories Differently. We had a fascinating discussion, so let’s just get right into that, shall we?

Jared: Absolutely. And I just want to say, we don’t usually plug books like this, but just a really great book, so we are going to plug it – The Bible With and Without Jesus, pick it up, but first listen to this episode.

[Music begins]Marc: The Bible is not important in Judaism; the Bible interpreted is important in Judaism.

AJ: Of course, they were confused! And of course, Christians today are confused. We forget that Paul’s not writing to all Christians; Paul is writing to a first generation group of gentile Christians who are trying to figure out what it means to live in this new messianic age.

[Music ends]Pete: Well, AJ and Marc, welcome to our podcast! Again!

AJ: We are delighted to be back.

Pete: Yes! We’re so delighted to have you back, it’s fantastic. So, okay, listen, let’s get right into this topic. You might not know this, but there are both Jews and Christians living in the world, right? And they have this Bible, and they read it differently. And you know, I think it’s such a wonderful exercise to get into to talk about why Jews and Christians read, really the same stories, differently. And you know, sometimes it’s like you’re right and you’re wrong kind of thing, but I think the issues are much more complicated than that. So, let’s get into that. Why do Jews and Christians read the same stories differently?

Marc: I’m glad you’re not asking it in terms of we’re right and you’re wrong or vice versa, because that is exactly the opposite of what we’re trying to claim. We never read without a context; we’re always reading things in a context. One of the first things to consider is that Jews and Christians have very different contexts in a whole bunch of ways. So, for example, when we’re talking, when AJ and I are talking about reading the Bible, we’re talking about reading the Hebrew Bible, which one of the names Tanakh, another name Old Testament, another name is, we have a whole podcast on the different names for this particular book. Not that the name of the book is different, but that whether the book is a self-standing book or not and what other literatures it relates to. Those are truths that are fundamentally different in the different cultures. So, when a Christian reads the story, you might start at the beginning of Genesis – the story about the creation of the world, the story about the creation of Adam. In the Old Testament, well, that Old Testament he or she is reading is part of the larger Christian Bible which includes the New Testament which has some very specific traditions and beliefs about what those passages mean. A Jew, on the other hand, when reading those passages will be reading it in the Hebrew Bible as more or less a self-enclosed world. I’ll come to that more or less in a second, but is certainly not reading it in reference to the New Testament and might be

reading it a little bit, depending on which Jew it is, in relation to later Jewish tradition.

4:58

So, that is one of the ways in which Jewish and Christian readings of the same words will differ. I want to mention one more, then I’ll let AJ pick things up from here. Often, we’re also reading in different languages. Jews are reading it in the Hebrew. That is what is fundamental to the Jewish understanding of the Bible, or in some cases a couple of chapters in Aramaic which is one of the reasons we don’t like using the word “Hebrew Bible” to describe this particular text. And we will go back to the Hebrew, and we’ll go back to a particular Hebrew text and the Masoretic Text, which has been traditional within Judaism for over a millennium. We’re not going to go back as Jews. Jewish scholars will be a little different, but as Jews, we’re not going back to the Dead Sea Scrolls. And that’s, you could see for example, if you look at a passage concerning Saul in the book of 1 Samuel and you compare the Jewish Publication Society translation to the New Revised Standard Version of translation, the Protestant Bible has a whole bunch of verses which are found in the Dead Sea Scrolls, which just aren’t there in the Masoretic text. We’re not even always reading the same Bible itself.

AJ: Well, that was a great start Marc! Thank you! So, why do Jews and Christians read differently? Well, just corollary, not all Jews read the same way. You know, heaven forbid. And Marc and I don’t always agree, and we have to hash some of this stuff out. But let’s see, not only are we reading it in different languages – so, Jews to this day are still in the synagogue reading from the Hebrew and indeed from a scroll rather than from a book. So, think about the difference between reading from like a book that you hold in your hand as opposed to reading online or on a Kindle. We punctuate differently because ancient Hebrew doesn’t have vowels. So, just as an experiment, you put the letters “gd” together and you can get God or good or egad or, if you’re generous, goody. So, we have to figure out what the vowels are in there for what the words mean. We have a different reception history because when, for example, the New Testament cites Isaiah 53 in terms of the person who bore our diseases and was wounded for our transgressions. They’re going to come up with Jesus (that would be obvious) and the synagogue has come up with 15 or 20 different possible candidates for that suffering servant. We read with a different anthropology because Christians typically, traditionally, start with the idea of a fall in the Garden of Eden that had to be rectified and Jews don’t talk about a fall and we don’t talk about an original sin. We might rather talk about an original opportunity, but there’s no irreparable breach between humanity and divinity such that Jesus has to come and fix it. We emphasize different portions of the scripture. So, for Jews the book of Esther is enormously important – it gets an entire holiday. And pretty much on Sunday morning, the only time one hears the book of Esther is on something like “Church woman United Sunday” where you hear “you have been chosen for such a time as this.”

Pete: [Light laughter]

AJ: So, different reception histories, different emphasis, different language, different punctuations, different canonical order – we’re not reading the same Bible at all! And that actually is pretty good, because then we don’t have to wrestle over I got it right and you got it wrong, we can say, well, we may be reading the same stories but we’re reading them so differently in such different versions that we can actually share these readings with each other and figure out what we can agree upon and places where we will have to agree to disagree.

Marc: Let me just pick up on something that AJ just said and develop it a tiny bit more.

AJ: I should note that we do this all the time, by the way. We’ve gotten to the point where we finish each other’s sentences.

Pete: Okay.

[Laughter]Marc: Which would be really good when the internet cuts out, but I hope not today. The issue of canonical order is really, really important. What is the climax of the Hebrew Bible or the Old Testament? Is it the book of Malachi as it is in the Christian order which talks about the coming of Elijah the prophet and this is a wonderful, climatic segue way into the New Testament? Or is it, you know, the book of Chronicles, which ends with the Cyrus declaration and welcomes the Judeans or Judahites back to their land and emphasizes the importance of land? From the Jewish perspective in terms of reading this very same book. And also, just to go back to AJ’s issue of emphasis, I have a visual image which I think some of your listeners might enjoy.

9:50

Even if we’re reading exactly the same text, which we aren’t, but let’s for a moment imagine that we are, Jews and Christians, in essence, are at different words or different chapters or different books in different sized fonts. So, to pick up on what AJ just said, for Jews, Esther is a 48 font, 48 point font book. For most Christians, it’s a 10 or 12 point font book or sometimes it’s the reverse. For Christians, the description of what is called, this term never appears in the Bible, the suffering servant in Isaiah chapter 53, you know, it’s going to be 48 or maybe 60 point font. Most Jews have never read this chapter –

Pete: [Laughter]

Marc: Have never heard of it. It’s not as if we’re taking it out of the Bible, but in the way which Jews read the Bible, you know, maybe it’s an 8 point font or we’ll be generous and give it 10 or 12 points. So, how significant each faith community takes various chapters or sections of the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament is another area where we differ very, very significantly.

AJ: Or just more broadly. I’m doing it! I am finishing these sentences.

Pete: [Laughter]

AJ: Just more broadly, the synagogue is going to concentrate on the first five books, the Torah, which means Leviticus is really important, Numbers and Deuteronomy. And you really hear that stuff in churches, particularly on a Sunday morning. The church is more likely to be preaching, if it’s doing it’s “Old Testament preaching,” more likely to come from the prophets. So, even when it comes to Pentateuchal materials, we all like Genesis, but the promise of the land that Jews hear over and over again frequently drops out of Christian liturgical formulation. So, differences all over the place so that when we start talking with each other, Jews and Christians, about what strikes us in the Bible, we frequently miss because what the Jew finds important, the Christian may find irrelevant or not know very well and vice versa. So, one of the things Marc and I are hoping is that Jews and Christians will read these texts together and then be able to see what the meanings are in the eyes of our neighbors and that actually helps us know our neighbors better. And if we’re lucky, when our neighbors give us their perspective on the text, we get to know our text better as well.

Pete: Hmm.

Marc: And I would just say from the beginning of your question, you asked us about reading the same stories differently. I just want to point out that Jews and Protestants, let’s leave aside the issue of translation, are more or less reading the same stories, reading the same stories. But on the other hand, if you want to talk about Catholics and people in the Eastern church, the text of Esther is different, it has a number of what are called additions that you can sometimes find in the Apocrypha and same thing is true for the book of Daniel. So, I often like imagining that a Jew and a Catholic are talking about the book of Esther right after the festival of Purim and the Jew says, you know, “What a strange book we have. God isn’t even present explicitly in the book.”

Pete: Mm hmm.

Marc: And the Catholic can come and say, “I’m sorry, I just read it a few weeks ago and I saw a handful of references to God.” So, we’re not even always reading the same book.

Jared: Well, I wanted to talk a little bit, not to get too granular, but one of the things I appreciated in your book is you talk about what I would call like, the slipperiness of language. Just that language itself is ambiguous, you know. AJ, you mentioned the consonants and vowels and how there aren’t vowels. So, there’s just this ambiguity of the text that allows for these different traditions and I just wonder if you could say a little bit more about how we can get so many different meanings out of, well, we have very different texts and we talked about, you know, the stories can be different and there’s different verses and different chapters inserted here and there, different traditions do that, but even when we’re reading the exact same story, we can come up with different meanings and that seems to be inherent in how language works, but maybe you can say a word or two about that.

AJ: Or its inherent in how human imagination works. I mean, even today, if two people watched the same television show or streamed the same movie, they might get very different impressions out of it. Oh, this is an allegory/that was supposed to be funny, I didn’t like it/I thought it was brilliant, and so on. And so, as human beings we’re attuned to stories and as we’ve seen particularly recently in the United States, we’re also attuned to laws and how you interpret laws. That’s why we have people like lawyers and TV commentators. So, if you have a law that says don’t murder, then you have to figure out what constitutes murder and does that include manslaughter or self-protection or whatnot. So, interpretation is part of the human condition and interpretation is required for any text that we read, because otherwise we’ve just got dots and dashes on a page and we have to figure out what to do with it. Making it more confusing is that all translators are traitors –

Pete: [Chuckles]

14:50

AJ: Because every time you translate something, something goes out that was in the original in terms of connotation or word association, and something usually drops in that wasn’t. So, among our really good examples of this is the different way we read Isaiah 7:14, which in the Hebrew, the prophet says to the king, “hey! See that pregnant young woman over there. And let’s talk about her kid and we’re going to name him Emmanuel.” Well, it’s not actually clear who names him, and by the time he can eat solid food, your problems are going to be over. And that’s in the Hebrew which just talks about a pregnant young woman, but when you get into the Greek, the term for young woman comes in with a term that can be translated young woman but can also be translated virgin. And now we’ve got something else to talk about.

Marc: Yeah. Let me add a general point and two more examples to what AJ just said. So, in terms of your question, many people see the slipperiness of language, I think that was your term, as something negative. I think we see it as something positive and I think that often religious tradition, and especially Jewish religious tradition in interpretation sees it as something positive. Something else that needs to be considered – the vocabulary of biblical Hebrew is tiny when compared to the vocabulary of English. So, therefore, many words naturally have homonyms because you have fewer number of words but have to talk about the same human reality. So, we have real problems in language. So, let me just give you an example of that and then I’ll talk about another area of slipperiness. Genesis 1:2 where you have the phrase, listen to the beautiful alliteration – ve ruach elohim merahephet al-pene hammayim. The ruach of God was hovering on the face of the water. Well, here, ruach in many cases of the Hebrew Bible refers to the physical winds. On the other hand, ruach is also the word which is used for spirit and Hebrew does not have a separate word which distinguishes spirit from wind. So, that word is naturally slippery or naturally ambiguous and you guys have to use your textual hints and understandings context and so forth to understand what Genesis 1:2 might have originally meant. And again, something that we both emphasize is you know, we’re not total originalists. We are interested in what the text originally meant, but we don’t mean to say that all people of all religious traditions need to abide by what the text originally meant. Let’s take advantage of what you called the slipperiness. So, that’s one type of ambiguity that you have. Something that we haven’t talked about yet is the issue of punctuation. The original Hebrew text has no punctuation and it’s really not until the end of the first millennium of the Common Era that a system of cancellation, of how the word should be accented, which would also connect it to a system of punctuation entered into the text. So again, let’s take an example that’s relevant for the New Testament from Isaiah 40:3. I’ll just read the first four words in Hebrew, “qol qore’ bammidbbar pannu”. Okay, the voice calls out into the dessert, make way. Well, is the voice calling out in the desert or the wilderness, which is the reading that you have in the New Testament – or is the voice calling out; telling people to make way in the wilderness? Well, you don’t have punctuation, then you have no clear way of arbitrating, in most cases, between such readings and you have either slipperiness or wonderful ambiguity.

Pete: So, does the quotation mark begin with in the wilderness?

Marc: Yes, that is a good question.

Pete: Yeah. That’s the issue, right?

Marc: Yeah. Or is the voice calling out in the wilderness?

Pete: Right, right.

Marc: Both of those are possible. Thank you for the clarification.

Pete: Yeah.

Marc: And maybe we can celebrate rather than fight.

Pete: Well, I wonder are they both, I guess they’re both possible, but it really seems from just the structure of that verse, that it really means a voice calling out, “in the wilderness.” Right? Do you agree with that, or do you see it differently?

Marc: No, I agree that, let me phrase it this way, that the interpretation not found in the New Testament is the more likely original interpretation.

Pete: Okay.

19:45

Marc: The structure, the verse, what’s called the parallelism of the verse, implies that the wilderness is where you are preparing the way for the Lord.

Pete: Mm hmm.

Marc: But that is not the only possible interpretation and clearly the fact that it was interpreted differently by some 1st century Jews suggests that even in the 1st century there were different understandings of this should be understood.

Pete: Mm hmm.

AJ: It’s a matter, in part, of what we want scripture to do because scripture is not just, we don’t talk about, like, you know, Homeric scripture or Virgilist scripture. Scripture is not just a historical document for which a bunch of historians with a bunch of Ph.D.’s can go back and say, “oh, this is what Isaiah originally intended,” if we could determine that. But scripture also has to speak to the communities that hold it sacred, which means it cannot only mean what it meant to its original audience. We’re always asking from a scriptural perspective what does it mean to me today or what does it mean to the covenant community at such and such a time. So, if it only meant what it meant in its historical context, there’d only be one sermon on it because that would be the original meaning, and we’d have no way of having the scripture communicate to us. This particular passage from Isaiah 40 really opened up for the church, because not only did it give a kind of background to John the Baptist out there in the wilderness proclaiming the way, but when the text goes from Hebrew into Greek and it’s the Greek primarily that the writers of the New Testament are using. When Mark picks this up, and I think it’s like the third verse of the Gospel of Mark –

Pete: Mm hmm.

AJ: It’s Mark 1:3, and it’s “prepare the way of the Lord.” Well, the Greek word for way is hodos, you know that from the word odometer, right? So, your mileage indicator? But according to the Gospel of Luke, the early followers of Jesus didn’t call themselves Christians. Jesus didn’t know that word, Paul didn’t know that word – that comes in really late. They called themselves followers of the way so that when Mark’s readers read, and when Mark’s Christian readers read “prepare the way” they go, “oh! That’s the way of Jesus because that’s what we call ourselves.” So, clearly that’s not what the word meant when Isaiah was talking to a bunch of people in Babylon in the 6th century BCE, but clearly it did mean that to the followers of Jesus in the late 1st and early 2nd centuries. And that’s that idea of words changing meaning over time. And we see that even today, where books that we might have read with no problem fifty years ago, well, at least for those of us who are that old, we read today and we see the racist language and the sexist language and we cringe because we’ve got a different context by which to understand literature whether for better or for worse.

Pete: Hmm.

Jared: That brings me, maybe you can talk a little bit about this bigger picture idea of the interpreted Bible. It’s something that you guys come back to again and again, and I just, I want to make sure we don’t miss it because we’ve been, we’ve been definitely weaving that idea in throughout our conversation. But maybe let’s take a step back and just talk about what you mean by an interpreted Bible and how that impacts how we come to the text.

Marc: Well, there’s no such thing as an uninterpreted Bible.

AJ: Unless it just sits on your shelf, right, for decoration. That’s an uninterpreted Bible.

Marc: Yeah. There’s a wonderful story of a Hebrew Bible colleague of mine, Ed Greenstein. He taught for many years at Jewish Theological Seminary then at Tel Aviv University and Bar-Ilan University in Israel where his students – I’m going to get this story almost right – where his students used to complain that he cared too much about theory and that they just wanted to hear the text speak. But one day he came to class, he walked in at the appointed hour, he opened his Bible and went silent for five minutes. The students, you can imagine, were getting more and more perplexed. Then finally he explained, well, I was trying to let the text speak for itself.

Pete: [Laughter]

And lo and behold, it didn’t. So, anyway.

[Continued laughter]AJ: This is the point where you want Charles Heston’s voice to come in through the speaker, right? That would’ve done it.

Pete: [Continued laughter]

Marc: Especially in some theological worlds there is a notion of an uninterpreted Bible, but on everything, on every word, every phrase, we are making interpretive judgments. We are deciding which of the various meanings are homonyms or slight shades of difference. We are deciding what is the syntactic relation in a particular phrase, what is the subject, and what is the object? And those are all interpretations that we need to make in order for the text to make sense.

Pete: Yeah.

24:49

Marc: I once wrote something which people got a little angry at me where I said, you know, the Bible is not important in Judaism – take a breath – the Bible interpreted is important in Judaism. And I will stand by that, and I think that’s the case for Christianity as well and I think of it as the case for any literature.

Pete: Mm hmm.

Marc: Like, a grocery list, in some cases, can speak for itself. Not all the time, we’ve all had times where, you know, we’ve come back and our spouse has not been so happy in how we interpreted that particular grocery list, okay? But any literary text cannot speak for itself and requires interpretation.

AJ: I wonder if it’s a problem with the questions that we ask so that sometimes students will say, “what does this text mean?” And that’s probably not a very good question. You might have to gloss that. What does it mean to me today in my current situation? What did it mean to people in the 1st century? What did it mean to people in the 15th century? What does it mean to a historian? So, the text that we’re looking at which are primarily the so-called shared scripture, like Genesis or Isaiah or Jonah, we can already ask three different questions here. What did it mean in its original context as best as that meaning can be reconstructed? How does it get picked up in the New Testament, and even there it’s going to have multiple meanings. So, the suffering servant certainly refers, in some texts, for example 1 Peter, to the suffering and death of Jesus on the cross. But in the Gospel of Matthew, that suffering servant represents Jesus the healer who takes peoples diseases and cures them of that. It also tells us that pre-healthcare is a miracle. And what does the suffering servant then mean in Second Temple Judaism, the time of the New Testament, but by Jews who were not part of the Jesus movement, and what did he mean or they mean, because sometimes it’s looked at as the community of Israel, in later rabbinic thought and later medieval Jewish thought? So, you can’t just stop at what does it mean, you have to gloss that. What does it mean for whom and when?

Pete: Yeah, I mean, all these things are tying together with something. I think that you said earlier, Marc, you used a very interesting phrase that I think is very intriguing about taking advantage of the slipperiness of the Bible itself. You know, there’s no “clear, unambiguous, obvious” meaning. You have to work for it, but it’s more than that. You’re talking about taking advantage of the slipperiness and maybe, could you riff on that a little bit more because I think that’s taking a problem typically, I think for a lot of people listening to the podcast it’s taking a problem, “oh no! We don’t know exactly what this means!” And you’re turning that into more of an inevitable possibility.

Marc: Yeah, I mean, maybe I said, like the person trained in business who had a problem that was supposed to become an opportunity. But I really do believe that this is an opportunity and here is where I would start with the following statements – if the Bible (and here, I could be talking about the Jewish Bible, the Christian Bible, it doesn’t matter) was crystal clear and was univocal (in other words, spoke in one clear, consistent voice) and its interpretation was crystal clear, it would not have survived. Because part of what makes scripture, scripture, is its ability to speak to its unity in different times and different places. So, here, let me just, let me stick to the Hebrew Bible that I know better. Okay, so this is the book which is more than 2000 years old is written in the ancient Near East where life was very different, where technology was very different, and so forth. If we only took it as a book which was written for that particular generation in a language that that particular generation could understand, it would’ve been totally obsolete for us. Scriptural texts, by their nature, require flexibility so that they’re able to adapt to different times and places. You know, of course one very good question which theologians need to ask, and that’s another word that I use it myself, is to what extent do we adapt scripture to our own situation making it more flexible as opposed to what extent do we need to be more flexible adapting ourselves to the more ancient situation of scripture? That’s a difficult question. I’ll leave that for theologians.

29:54

But I’ll still stand by my statement that if it were a crystal clear univocal book, it would not have survived.

Pete: Mm hmm.

AJ: Nor would it have survived without that type of interpretation because people would’ve looked at part of it and said, “oh no, I’m simply not going there.” So, one of the things that we do see in Judaism and Christianity, because I am interested in questions of law. Like, you know, how do we govern ourselves? We’ve got that eye for an eye which is typically cited, and Paul is the major reason why people are in favor of capital punishment because, you know, the “Old Testament” says an eye for an eye. When Jesus evokes that passage in the Sermon on the Mount he says, “you have heard it said an eye for an eye,” and then he proceeds to change the subject, right? So, he goes from, he except, if somebody slaps you on the right check, turn the other. Well, that’s not, I mean, an eye for an eye means somebody actually takes out your eye, and there’s a big difference between losing a limb and getting slapped on the cheek. And rabbinic tradition says, oh, well, since no two eyes are equal, this has to be a legal principle that says in the case of actual physical injury, there should be some sort of compensation and then they work out a formula for pain and medical expenses and so on. So, the text shows us that it’s necessarily interpreted right from the get-go and even something that might be really clear, like an eye for an eye, isn’t.

Pete: Mm hmm.

Marc: And I just add to that, that one of the big contributions of biblical studies in, let’s say, the last 40 years or so is what is often called inter-biblical interpretation. There are different words we could use for that, but that shows that within the Hebrew Bible itself earlier books, which are now part of the Hebrew Bible, have been interpreted. So, Deuteronomy interprets sections of Exodus. Chronicles interprets sections of Samuel/Kings. In a variety of places, several Psalms interpret the promise of an eternal dynasty to David that is found in 2 Samuel 7. So, interpretation is embedded in the earliest form of scripture and therefore you’re going to take scripture seriously, then we need to take the fact of its naturality of interpretation and necessity of interpretation seriously as well.

Jared: I think that’s a really good point, because we often talk on this show about how, you know, we want to follow in the Bible’s trajectory and what we see it doing within itself. And, so maybe, can you do a deeper dive on, I’m thinking of this phrase you use, you know, of revelatory exegesis or revelatory interpretation where there’s, you know, God reveals a new meaning or a new interpretation to our community based on these older texts. So, is there a specific text that you can maybe dig into where we see the Bible doing this?

Marc: The clearest place where this appears in the Bible is in the ninth chapter of the book of Daniel. Where there Daniel is just introduced in verse two, so I’m gonna translate loosely from the Hebrew. “In the first year of his reign,” (and it’s referring to the previous verse to Darius) “I, Daniel, was contemplating the books. Concerning the number of years, which the word of the Lord was to Jeremiah the prophet, to fulfill the destruction of Jerusalem, seventy years.” Okay, now let me point something out. Seventy, this is based on a prophecy you have three times in the book of Jeremiah. The most famous is in Jeremiah 25 which suggests Babylonian world domination for a 70 year period. And 70 years, nothing could be clearer than 70 years. It’s like saying that your tax returns need to be postmarked by midnight of April 15th assuming it’s not a weekend. Okay? So, you can’t call down to the IRS and say, oh, April 15th, I thought you really meant May 28th. Okay? You could try, but I don’t think that that is likely to be very successful. So, he’s thinking about that, he’s praying over that, there’s a beautiful prayer that you have there and eventually in that very same chapter, this is why it is called revelatory exegesis, there you have in verse 21. So, I’m still speaking by prayer, this is Daniel speaking, “and the man Gabriel, whom I had seen in an earlier vision, flying around touched me at the time of the evening offering.” And then he explains that the meaning of 70 is 490. So, give me a minute. I need to explain this. So, in Hebrew, again, let me go back to AJ’s point, that in his period Hebrew was written without vowels.

35:00

So, in Hebrew the word for shiv’im that is used in those places in Jeremiah is shiv’im, normal way of saying 70. But, those same consonants, five or six consonants, can also be read as shavu’im, weeks. Now, in this prophecy in Daniel 9, the angel Gabriel tells Daniel, oh yeah, why don’t you read the word twice. Why don’t you read it first as shiv’im, seventy, then as shavu’im, weeks, and multiply 70 x 7, and you get 490 years. Now, what this does is it give Jeremiah’s prophecy a 420-year extension, right? Because 490 – 70 is 420. Why is this necessary? Because the book of Daniel is written from the scholarly perspective, and I firmly believe in this, in the second pre-Christian century under the time of the persecution of Antiochus IV Epiphanes where Jerusalem was not doing well at all. And it seemed like Jeremiah’s prophecy had not been fulfilled. So, through this revelatory interpretation, through the angel Gabriel, Jeremiah is given a 420-year extension. And this type of revelatory interpretation is very important in this period. We see it in a large number of books which are called apocalyptic books, in which these intermediaries (that’s probably a better term than angels) who explained divine will to people are also the people who explain what the text really meant.

AJ: That was a great example Marc. Just for another example, text that would not have been looked at as prophecy become prophecy when, for example, Jesus followers or the later rabbinic tradition start reflecting back on them. So that when Jeremiah, because he’s a good source for a lot of this stuff, when Jeremiah reflecting on the Judahites who were being taken into exile in Babylon and being marched past the tomb of the matriarch, Rachel. Jeremiah talks about Rachel weeping for her children because they are no more. Well, that’s not a prophecy, that’s a statement of fact that Jeremiah is witnessing, historically speaking. But when Matthew reads that text, Matthew puts that text as a commentary on what’s called the Slaughter of the Innocents, when King Herod the Great finding out that there’s this new child who’s being identified as King of the Jews. And Herod, who calls himself King of the Jews, finds this a bit problematic because he thinks there can only be one and that should be he, arranges to have all the children of Bethlehem slaughtered. So, when the children are slaughtered, Matthew says this was done to fulfill what was said by the prophet – Rachel, weeping for her children because they are no more. So, for that, for Matthew, Jeremiah speaking to his own historical context as a statement of fact becomes, in effect, a prophecy which is then fulfilled in the lifetime of Jesus. And that happens over and over again in the New Testament when you get “this was done to fulfill what was said by so and so,” and not necessarily prophetic material. So, the prophets are continually being redeployed for making statements that clearly are anchored in their own historical context into making statements that look forward 700 years, 800 years, 500 years, and so on, and the Jewish tradition will do the same thing.

Pete: Yeah, that’s part of just what happens, right AJ? This is the bringing of this ancient text into our present moment and so you take historical statements, and you turn them into prophecies.

Marc: And it’s more than that.

Pete: Okay.

Marc: Because it’s not only historical statements, it’s entire books like the book of Psalms. The book of Psalms originally was a prayer book, but let’s take Psalm 2 for example, where you have the nations gathering together in Psalm 2:2, “against the Lord,” ve `al-meshiycho, “and against his “Messiah.” Sorry, you can’t see me – I put the word messiah in air quotes.

Pete: [Laughter]

Marc: Because in the Hebrew Bible, the Old Testament, the Hebrew word mashiach never means Messiah. The word anointed, mashiach Christos, never refers to the future ideal Davidic king.

39:47

But for the early church that original meaning was not important, and the original use of Psalms was not important. And therefore, a chapter like Psalm 2 in the New Testament and even at various points in later Christian tradition, is understood as a prophecy about Jesus.

Pete: Mm hmm.

Marc: So, that’s another way in which a whole book shape changes as a result of understanding it prophetically.

Pete: Yeah. Well, and not to open up a whole other can of worms here, but again, I’m thinking about a lot of our listeners, just to bring Paul into this a bit. You know, he took his scripture very seriously and he was always, reading Paul’s use of his scripture is, you’re sort of on a hermeneutical adventure at that point, because he’s doing all sorts of interesting things. And I have found that it’s a tough thing for many Christians to look at and to sort of come to terms with that Paul is really doing some very creative things with the interpretation of this text which is right along the lines of all the stuff we’re talking about here in this episode.

AJ: He turns the story of Sarah and Hagar into a complete allegory where Sarah, whose name doesn’t get mentioned, this is Galatians 4. Sarah, she’s our mother above and it’s spiritual and she represents these gentile believers who have come into the Jesus movement, this messianic movement apart from Jewish law, which is entirely appropriate. And then Hagar is the slave based out on Mount Sinai and she represents these gentile believers who were still under the law. I don’t think other 1st century Jews are going there.

Pete: [Laughter]

Ya think?

AJ: You can take Sarah and Hagar and say they represent this or they represent that, and there are multiple stories about Sarah and Hagar in rabbinic literature. And here we have to worry about what Paul is doing. So, if Christians today are confused by Paul’s redeployment of what gets, what the Christians would call the Old Testament, you can imagine how his first converts felt, because those converts to whom he is writing in Galatia or in Philippi or in Thessalonica, they’re gentiles, they’re pagans! So, they’ve got a really big learning curve here because they’ve got to get a copy of the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the scriptures, and then Paul has to tell them how to read it. And these poor folks, they’re reading in Genesis, you know, unless you are circumcised in the flesh of your foreskin, you’re cut off from the covenant. I’d like to think that’s a pun, I can’t prove it, but I think so.

Pete: Oh yeah, I hope.

AJ: And they’re going, you know, so maybe we should do this. And Paul says, no, no, no, no, no! Because in the messianic age, one of the signs of the messianic age (this comes from Zachariah and from Isaiah) is that the gentile nations, the pagans would turn toward the God of Israel, but they don’t convert to Judaism because then the only people who would be worshipping God would be Jews. So, you’ve got to have pagans here, and now you can’t see me, but I’ve got my hands up. They’ve got to have pagans here and Jews here and together as equals they’re worshipping the God of Israel, but the Jews are doing it through Torah law and the pagans are doing it through their faith in Christ, and this Christ figure is uniting them all in this messianic movement. So, on the one hand, you’ve got Paul quoting this “Old Testament” scripture over and over again. Paul would never have used the term because there’s no New Testament yet. And at the same time saying, but here’s what it means, and it doesn’t mean what you think it means. Of course, they were confused! And of course, Christians today are confused, and part of that comes from the fact that we forget that Paul is not writing to all Christians, Paul is writing to a first-generation group of gentile Christians who are trying to figure out what it means to live in this new messianic age.

Marc: Let me come back to one word, which you said earlier, namely the word redeployment, which is a super important and super useful word. And let me just mention that what is happening in the New Testament in terms of redeployment of the Hebrew Bible, that was part of 1st century interpretation. So, when many people talk about Christianity in reference to the Dead Sea Scrolls, they often think that we’re looking for John the Baptist or Jesus in the Dead Sea Scrolls. And you’re welcome to look, you’re not going to find either of those figures in the scrolls. But what you do find is precisely this type of redeployment use of the Hebrew Bible. This has been known for a long time, one of the earliest scrolls which was discovered and then disseminated is called Pesher Habakkuk. It is a one of several pesher texts and the way which pesher’s work is they redeploy texts. So, the book of Habakkuk, if you read it, is about the Assyrian enemy of Judah, but that it’s totally redeployed in the pesher in reference to the Romans.

44:53

So, the way in which the Christian authors, whether it’s Paul or Jesus, understand the old text in reference to their contemporaneous situation was very much a part of at least one brand of interpretation that was common in the 1st century of the Common Era.

Jared: Well, I say this I think every episode that I say, unfortunately we need to wrap things up. But I really mean it this time, that it’s very unfortunate.

Pete: [Laughter]

You never meant it before?

AJ: [Laughter]

Jared: It’s very unfortunate because I feel like we could just keep this conversation going, it’s all so, not just fascinating, but I think really helpful. So, if we can end with one question, which would be for all of our listeners who some of these things may be new for them, what would be a word of advice now as they go into their communities of faith, as they read their Bibles – what would be one helpful tip or one practical thing you can leave with them?

AJ: I’ll start. When you read, don’t default to some sort of lowest common denominator where you and everybody else will come to some agreement on something that will wind up being really quite banal. Don’t sacrifice the particulars of your own tradition on the altar of interfaith sensitivity. Jews are going to read as Jews; Christians are going to read as Christians. Messianic Jews will be somewhere in between, but at least open up to the possibility that although you do not agree with the person who’s not part of your community, you don’t accept that particular reading, at least be able to understand the logic where it came from rather than just say, “oh, that’s nonsense” or “if you’d simply read more closely, you’d see the truth of,” to grant that it might not be your reading. But it’s nevertheless a reading with its own logic, its own history, and its own meaning to the individual and the community that preserves it.

Marc: And I’m going to follow the example of the Bible, which keeps rewriting itself in different ways, and I’m going to conclude with a quote which is attributed either to George Barnard Shaw, Winston Churchill, or Oscar Wilde depending on where you read it –

Pete: [Laughter]

Okay.

Marc: Which is – “England and America are two countries separated by a common language.” And I’d like to revise that to say Judaism and Christianity are two religions separated by a common scripture. And I think our job is to really understand what we have in common and to emphasize that at least as much as what separates us.

Pete: Well, and on that note, we sadly say we are out of time here, but this was so fascinating. I want to thank you both for taking the time. I know, Marc, you’re a little bit distant from us here today, physically, and AJ is a little bit too, but not quite as much. But thank you very much for being on our podcast, we had a great time talking about this very, very important, very timely, and not going anywhere issue of how Jews and Christians read the Bible differently.

AJ: Thanks for letting us talk about it.

Pete: Sure.

Marc: Thank you, and warmest regards from Jerusalem.

AJ: And from Nashville!

[Music begins]Pete: All right folks, thanks for listening to another episode of the podcast. And you know, you may have heard some words and some terms in this episode that need some explanation, and Jared and I do that. We do that after every episode, we call it the afterword, and you may have heard things like Tanakh or Masoretic or Aramaic or what other words, Jared?

Jared: Apocrypha, pesher…

Pete: Pesher, right. Things like that and Marc was throwing some Hebrew terms around, but this is where we discuss some of these things in more depth and sort of fill in some gaps and just have some great time together thinking about some of these issues, how they impacted us, and getting into some of the nitty gritty.

Jared: Yeah, so if you haven’t already, just check it out – https://www.patreon.com/thebiblefornormalpeople. It is the afterword, is what you’re looking for, where we take, you know, 10, 15 minutes to dive into these episodes with our guests and unpack some of the things we talked about. Thanks so much, we’ll see you next time.

Megan: We also want to give a shout out to our producer’s group who support us over on Patreon. They’re the reason we’re able to keep bringing podcasts and other content to you. If you would like to help support the podcast, head over to https://www.patreon.com/thebiblefornormalpeople,where for as little as $3 a month you can receive bonus material, be a part of an online community, get course discounts, and much more. We couldn’t do what we do without your support.

Dave: Thanks to our team: Executive Producer, Megan Cammack; Audio Engineer, Dave Gerhart; Creative Director, Tessa Stultz; Marketing Wizard, Reed Lively; transcriber and Community Champion, Stephanie Speight; and Web Developer, Nick Striegel. From Pete, Jared, and the entire Bible for Normal People team – thanks for listening.

49:58

[Music ends][Outtakes][Beep]Pete: The title of the book is, uh, Reading the Bible with –

[laughter]Dave, you’re going to have to edit this together.

[Beep]Pete: The title of the book is Reading –

Jared: It’s not reading. Oh gosh.

[Beep]Pete: The title of the book is, Dave, I’m so glad you’re alive and you can just splice these things together.

[End of recorded material]