Speaking of evolution and Christian faith . . .

A crucial question to ask ourselves is: what have we the right to expect from the biblical origins texts? I call “genre calibration” in The Evolution of Adam.

“Outside” information can “calibrate” the expectations we bring to the biblical texts in question.

This isn’t as odd a claim as you might think. Study Bibles are full of notes that do this very thing, as are seminary and college Bible classes. Whenever we read the Bible against its historical backdrop (i.e., reading it in a historical context), we are using that backdrop to affect our understanding of the biblical text.

When it comes to creation texts, part of the backdrop involves (1) the context of the biblical world itself (other ancient creation texts) and (2) various fields of science that deal with origins (biological, geological, cosmological). So things like genomic studies, the fossil record, and ancient Mesopotamian creation myths help us see that the genre of Genesis 1-3 is not what we call science or history but something else.

What that “something” can generate a lot of heat, but whether myth, legend, metaphor, symbol, story, or some other label, the point remains: seeking from the biblical creation stories scientific and historical information is to misidentify the genre of literature we are reading—to expect something from these stories they are not prepared to deliver.

Which brings me to a rather important point: the findings of science and biblical scholarship are not the enemies of Christian faith. They are opportunities to be truly “biblical” because they are invitations to reconsider what it means to read the creation stories well—and that means turning down a different path than most Christians before us have taken.

Though, this would not be the first time Christians have had to divert their path from the familiar to the unfamiliar.

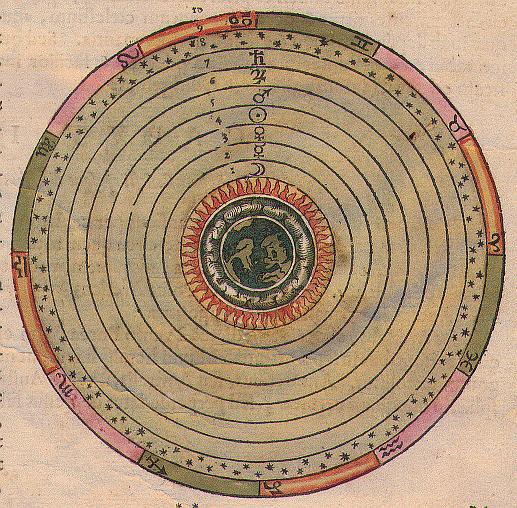

We need only think of the ruckus caused by Copernicus and Galileo, telling us the earth whizzes around the sun, as do the other planets, when the Bible “clearly” says that the earth is fixed and stable (Ps 104:5) and the heavenly bodies do all the moving. Sometimes older views do give way to newer ones if the circumstances warrant.

In fact, shifts in thinking like this are a perfectly biblical notion.

We find throughout the Bible older perspectives giving way to new ones.

The prophet Nahum rejoices at the destruction of the dreaded Assyrians and their capital Nineveh in 612 BCE, but the prophet Jonah, writing generations later after the return from exile, speaks of God’s desire that the Ninevites repent and be saved.

What happened? Travel broadens, and the experience of exile led the Judahites to think differently about who their God is and what this God is up to on the world stage.

In fact, Israel’s entire history is given a fresh coat of paint in the books of 1 and 2 Chronicles, which differs remarkably, and often flatly contradicts, the earlier history of Israel in the books of Samuel and Kings.

Why? Because the journey to exile and back home again led the Judahites to see God differently.

I could go on and talk about how the theology of the New Testament positively depends on fresh twists and turns to Israel’s story, such as a crucified messiah and tabling the “eternal covenant” of circumcision as well as the presumably timeless dietary restrictions given by God to Moses on Mt. Sinai.

What happened? Jesus forced a new path for Israel’s story that went well beyond what the Bible “says.”

Simply put, seeing the need to move beyond biblical categories is biblical—and as such poses a wonderful model, even divine permission—shall I say “mandate”—to move beyond the Bible when the need arises and reason dictates.

Being a “biblical” Christian today means accepting that challenge: a theology that genuinely grows out of the Bible but that is not confined to the Bible.

And so I see the matter of Christian faith and evolution not as a “debate” but as a discussion, not defending familiar orthodoxies as if in a fortress but accepting the challenge of a journey of theological exploration and discovery.

For me, that approach is much more than an intellectual exercise—though it is that—but a spiritual responsibility.