Today’s post is the second of three by Dr. Eric Seibert, Professor of Old Testament at Messiah College (post one is here). Much of Seibert’s work is centered on addressing the problematic portrayals of God in the Old Testament, especially his violence. He is the author of Disturbing Divine Behavior: Troubling Old Testament Images of God

Today’s post is the second of three by Dr. Eric Seibert, Professor of Old Testament at Messiah College (post one is here). Much of Seibert’s work is centered on addressing the problematic portrayals of God in the Old Testament, especially his violence. He is the author of Disturbing Divine Behavior: Troubling Old Testament Images of God (Fortress 2009) and The Violence of Scripture: Overcoming the Old Testament’s Troubling Legacy

(Fortress 2012). Seibert is also a licensed minister in the Brethren in Christ Church and formerly the Director of the Peace and Conflict Studies Initiative at Messiah College. He is currently working on his fourth book, Disarming the Church: Why Christians Must Forsake Violence to Follow Jesus (Cascade).

It is a truism to say the Bible contains a lot of violence. That much is obvious. Yet not all violence is regarded the same way in the pages of Scripture. Sometimes, the Bible makes it unmistakably clear that certain acts of violence are wrong.

No one who reads the story of Cain and Abel in Genesis 4, for example, is going to conclude that this passage is meant to encourage murder! Nor are people likely to read the story of David’s adulterous affair with Bathsheba and his deadly dealings with Uriah and conclude that we should “go and do likewise.” In fact, in this instance the narrator explicitly tells us that “the thing David had done displeased the LORD,” (2 Samuel 11:27, NRSV). Most of us would concur!

Stories like these, though troubling in terms of what they reveal about human sinfulness and our capacity to hurt others, are not problematic in terms of what they say about violence. In both cases, these narratives clearly demonstrate that the use of violence is bad and undesirable.

But what are we to do with passages of Scripture that sanction violence and portray it as something good? How should we regard what one might call “virtuous” violence in the text?

good? How should we regard what one might call “virtuous” violence in the text?

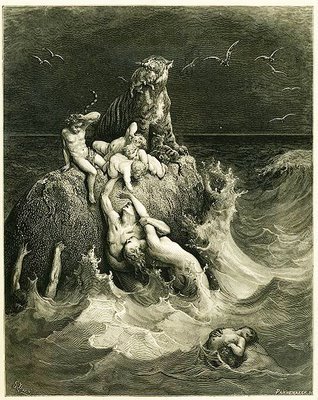

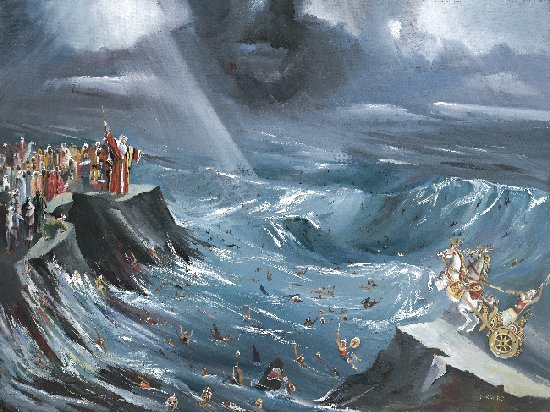

Examples of “virtuous” violence abound in the Old Testament and are embedded in some of its most beloved stories: the flood narrative (Genesis 6-8), the story of the ten plagues, culminating in the death of every firstborn Egyptian (Exodus 12), the drowning of the entire Egyptian army (Exodus 14-15), the “conquest” of Canaan (Josh 6-11), Jael’s slaying of Sisera (Judges 4), and David’s slaying of Goliath (1 Samuel 17), to cite just a few notable examples.

In each of these passages—and many others like them—lethal violence is condoned and sometimes even celebrated. Passages like these create significant problems for Christian readers.

Should we regard Jael as the “most blessed of women” (Judges 5:24, NRSV) because she drove a tent peg through Sisera’s skull? As we read about dead Egyptians washing up on shore, should we join voices with the Israelites and praise God for throwing “horse and rider” into the sea (Exodus 14:30-15:21)? Should we approve of Israelites killing Canaanites, massacring Midianites, annihilating Amalekites—including women and children—because they Bible says they did so with divine approval and blessing?

Or, to reduce these questions to the title of this post, “When the Bible sanctions violence, must we?”

My answer to that question is an unequivocal “No!” We should not, and we must not! It is extremely dangerous to endorse violent texts like these. Tragically, this kind of approval has often led to future acts of violence against others (as noted briefly in my previous post).

My answer to that question is an unequivocal “No!” We should not, and we must not! It is extremely dangerous to endorse violent texts like these. Tragically, this kind of approval has often led to future acts of violence against others (as noted briefly in my previous post).

As Christians, we have a moral obligation to critique the assumption that violence is somehow “virtuous,” in spite of what the Bible suggests on numerous occasions.

Violence is not a virtue. It is not a fruit of the spirit or a mark of discipleship. It is a behavior we attempt to avoid and restrain. Even Christians who believe violence can be justified in certain situations, such as protecting the life of an innocent person, must surely object to some of the violence that is approved in the Old Testament. There are no moral grounds for slaughtering babies, infants, or toddlers. Yet the Bible justifies their extermination on more than one occasion.

Surely, those of us who follow the prince of Peace, the God of Life, must raise our voices in protest and object. We must say, “This is not right!” Such violence is never justifiable and should never be condoned.

In my next post, I’ll talk a little bit about how I think we should go about confronting the problem of “virtuous” violence in Scripture. But for now, I’ll simply end with a question. I believe we should critique positive portrayals of violence in the Bible. Do you?