The older I get, the more I like–really like–Psalms and the wisdom books, Proverbs, Job, and Ecclesiastes.

Genesis through Nehemiah tells a story, a story of Israel, from Adam** to the return from Babylonian exile.

And the story–though deep, complex, and worthy of far more than a Tweet-sized summary–goes something like this:

God formed a people of his own, delivered them from slavery, and gifted them a land and the promise of his presence if they remain faithful to his covenant, to the law of Moses. Obedience ensures perpetual presence in the land (i.e., “life”) and disobedience ensures eventual exile from the land (i.e., “death”).

Israel’s main storyline is pretty black and white, a lesson to be learned, a story with a moral…

But for Psalms and wisdom literature, life isn’t black and white. Life is messy, unpredictable, and often makes no sense.

These books take issue with the storyline and its morals. They interrogate the black and white script and conclude, “Life isn’t that straightforward.”

- Job loses everything he has except his life. The script (e.g., Deuteronomy) says that such calamities are by God’s hand, a response to disobedience. Yet we learn from Job that this is not the case.

- Ecclesiastes

questions the “world order” God has made: nothing we do matters, since we all die and are driven to the point of madness at the thought of our futile existence.

- A number of psalms lament God’s absence in the world. Like Psalm 73–where the author can’t get his head around how a just God can allow the wicked to prosper.

- Or Psalm 89–where God is in effect called a liar for promising that one of King David’s descendants would always be on the throne in Jerusalem and then allowing the Babylonians to kill off the last of David’s royal line and take the people captive.

I like these parts of the Bible because, the older I get the more I live where the script makes less sense. Too much of life has happened. It’s all too messy.

Job’s experience threatens the foundation of his moral world. God punishes the wicked, yet Job isn’t wicked. So why is God doing this?

Job never gets a straight answer to the question–other than God telling Job “I’m God, the Creator. You’re not.”

I don’t take that to mean, “Be silent before the sovereign overlord, you puny human. How dare you question meeeee!”

I take it to mean, “You are human, Job, present here on earth for a few moments. You can’t possibly comprehend how the universe works, or my part in it. The script of the sacred story is fine as far as it goes, but this world and my place in it aren’t constricted by it. You will not figure this out, Job.”

Now, to get to my point.

For me, in my little private thought-world, the biggest reason not to believe in God in the conventional sense is the universe we inhabit.

Morality–discerning what makes up proper conduct toward others–is so very central to the human experience, and which people of faith ground in God’s goodness and justice.

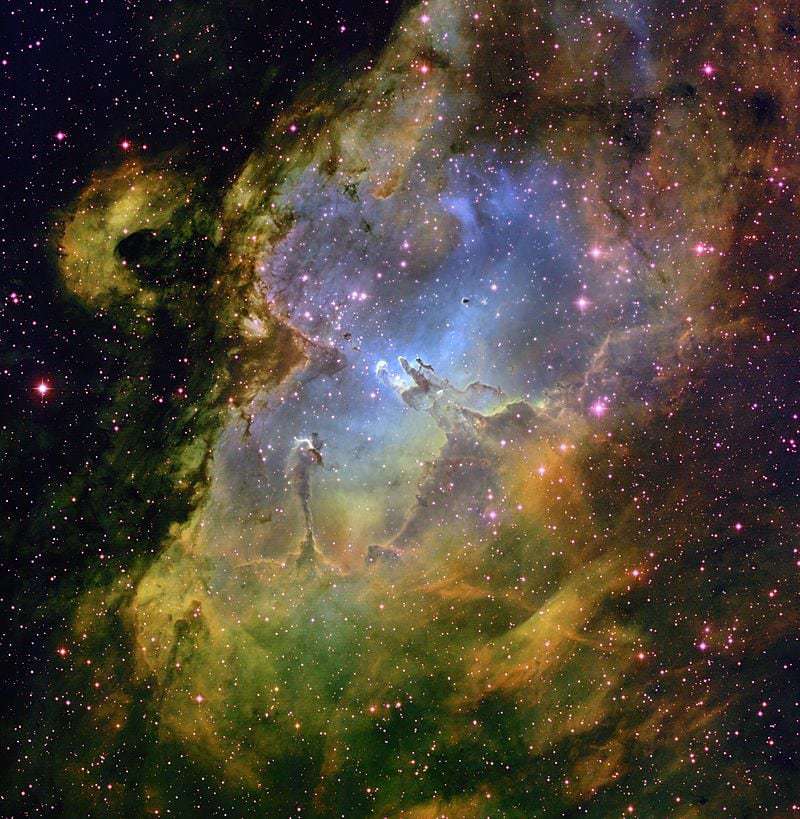

Yet the universe we inhabit is largely deaf to our moral preoccupations. It is distant, cold, empty space, beholden to an apparently endless cycle of destruction and rebirth.

Here on earth, tsunamis take out coastlands and tens of thousands of lives. Mudslides, hurricanes, tornadoes, and volcanoes hit with little or no warning. Our environment is hostile, and we know, despite what an occasional crackpot T.V. preacher says, that God doesn’t cause these disasters because America has ceased being a “Christian nation.”

Sentient beings kill and eat each other. The entire evolutionary process is fueled by suffering and death on a massive scale.

So what kind of God is this, who abides by this clash of interests–a God who is good and just, expecting the same from us, but whose universe operates by a different standard?

I’m not the first person to ask these questions and I have no interest in answering them here–though I think Job points us in the right direction.

God’s answer to Job, if I may translate into the contemporary idiom, is that the divine is “trans-rational.”

At the end of the day, the human thought process can only get you so far when it comes to God.

At some point, for most of us, as it was for some biblical writers, God stops making sense.

The question then is whether the non-sense leads to disbelief in God or becomes an invitation to seek God differently–even through confrontation and debate, as these biblical books model for us.

I know people who have answered that question both ways–people close to me, whom I love and respect. I’m not judging anyone and I’m not here to debate the issue or try to make an argument.

I’m just saying that over time I’ve come to answer that question in the second way–as I think Job, some psalmists, and the author of Ecclesiastes did.

Some might call that kind of faith “fideism”–an irrational belief in God rather than based on “sound reason.” But I think the charge of fideism misses the halting lesson life insists on giving us, and also persists in presuming what Job’s friends also insisted on–that where God is concerned, things make sense.

The issue as I see it isn’t simply whether your faith is or isn’t “reasonable.” “Reasonable” is a moving target.

The issue is whether we are able to accept that our cognitive power–which can be limiting and deceiving as well as liberating and enlightening–is truly up for the task of grasping the divine.

That, I think, is what these books of the Old Testament are after in their own way and in their own time and place. And that’s why I like them.

**I see Israel’s story beginning with Adam because I see the story of Adam as a preview of Israel’s story. As Adam was placed in a garden paradise and exiled from it because of disobedience, Israel was gifted the lush land of Canaan and exiled because of disobedience–but I digress.