Today’s guest post is by David W. Opderbeck, professor of law at Seton Hall University Law School, and Ph.D. Candidate, Systematic and Philosophical Theology, University of Nottingham.

Today’s guest post is by David W. Opderbeck, professor of law at Seton Hall University Law School, and Ph.D. Candidate, Systematic and Philosophical Theology, University of Nottingham.

One of Opderbeck’s area’s of interest is science and faith, and he likes to bring into the evangelical discussion the often neglected work of the Church Fathers. While studying at an evangelical seminary, Opderbeck was introduced to the notion of the “theological interpretation” and did some basic reading in the Church Fathers. He then began to study the Fathers more closely.

He came to appreciate how the practices of biblical interpretation from the early Church can help Protestants recover a more robust understanding of the scriptures, which can absorb new challenges and insights from the natural sciences without becoming defensive, and which also can help build bridges between diverse church traditions.

Opderbeck writes on complex matters in an accessible manner at his blog Through a Glass Darkly, and has also blogged on theology, law, and scripture at Jesus Creed (for example, here).

Over the past few years, I’ve had an opportunity to read some of the writings of the Church Fathers. I was particularly blessed to audit an introductory Patristics course at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary (Yonker, N.Y.) with one of the world’s leading authorities on their writings, Rev. John Behr, which covered Patristic writings prior to Augustine. I still consider myself very much a student and not an expert on Patristic writings, but here are some key things I’ve learned about theology and scripture from reading the Fathers.

The Fathers read the scriptures and constructed their theologies through the lens of the Church’s living experience of Christ. They did not use the scriptures to prove Christ. They used their experience of Christ to authenticate the scriptures and then used the scriptures to clarify their experience of Christ.

In fact, the Fathers began to define the canon of scripture from among a wide variety of early Christian writings based in large part on what they understood to be the central “story” of the universe (referred to by some of them as the “Rule of Faith”): the incarnation, life, death, and resurrection of Christ.

The Fathers knew that the scriptures are confusing, messy, and even self-contradictory. They did not impose upon the scriptures an expectation of rigorous systematic analytic logic. They understood very well that there is a finality to truth that inheres in the simplicity, unity and rationality of God’s own person as Father, Son, and Spirit, so that the scriptures ought to be interpreted to speak with a kind of polyphonic harmony.

The doctrines of the Trinity and Christology that were developing – and much debated – leading up to (and after!) the First Council of Nicea (AD 325) and the Council of Chalcedon (AD 451) also dealt with this same theme of unity-in-plurality.

The fulcrum for the Fathers concerning the doctrines of the Trinity and Christology was the same as for their interpretation of scripture: the Church’s living experience of and witness to Christ.

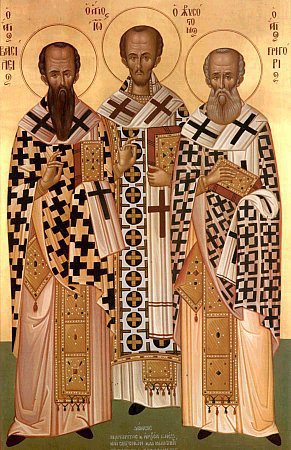

The Fathers knew that the doctrines of the Trinity and Christology they were attempting to articulate finally are mysteries. Nevertheless, they were rigorously philosophical in their efforts to articulate those doctrines. These were erudite, highly educated and sophisticated men (yes, the writers I’m referencing today were all men – but that is a subject for another day).

In fact, without some background in Greek philosophy, it’s impossible to understand much of what they were saying. Theologians today continue to debate the Greek thought categories the Fathers employed in the Nicene Creed and the Chalcedonian Definition.

Yet even with all their philosophical rigor, the Fathers themselves knew that their linguistic and philosophical categories were approximations or analogies for truths that finally lay beyond human comprehension. Their efforts to define these doctrines carefully were not so much attempts to state final truths as efforts to avoid idolatry and blasphemy – to avoid saying too much, and to avoid inaccuracy as much as is humanly possible. They knew this was necessary not only for formal doctrinal creeds and definitions, but also for the scriptures.

Just as the Trinity and the divine-human natures of Christ are mystical truths that defy the bounds of human capabilities, so the scriptures, for them, were mystical texts that point to something beyond the words on the page – that is, to the mystery of Christ.

Given their approach to theology and scripture, the Fathers were not univocal concerning how to  read many of the Biblical narratives, including the creation texts. Many of them thought the Genesis 1 and 2 narratives were in some sense mystical rather than “literal.” Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335-395 AD), for example, puzzled over the mention of two trees in the middle of the Garden of Eden:

read many of the Biblical narratives, including the creation texts. Many of them thought the Genesis 1 and 2 narratives were in some sense mystical rather than “literal.” Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335-395 AD), for example, puzzled over the mention of two trees in the middle of the Garden of Eden:

There was only one paradise. How, then, does that text say that each tree is to be considered separately while both are in the middle? And the text, which reveals that all of God’s works are exceedingly beautiful, implies the deadly tree is different from God’s. How is this so? Unless a person contemplates that truth through philosophy, what the text says here will be either inconsistent or a fable.” (Gregory of Nyssa, Sixth Homily on the Song of Songs).

It was common for the Fathers to take this sort of approach based on the nature of the text itself. As theologian Michael Hanby notes in his difficult but fascinating book No God, No Science: Theology, Cosmology, Biology, although we often think of John 1 – “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” – as a commentary on Genesis 1, “we must recognize that in the theological mindset of the early church and the Fathers, it is more appropriate to regard the opening verses of Genesis as a kind of commentary on the Prologue to John’s Gospel….”

That is, for them, the interpretive principle for scripture, theology, and indeed all of history and creation, was the living Christ.