Today we continue our 3-part series by Randy Hardman on his experiences as an official Christian apologist and why he felt he had to move on from that vocation. (The first part is here, with an important disclaimer. Readers interested in similar posts on this theme can find them beginning here, here and here.)

Today we continue our 3-part series by Randy Hardman on his experiences as an official Christian apologist and why he felt he had to move on from that vocation. (The first part is here, with an important disclaimer. Readers interested in similar posts on this theme can find them beginning here, here and here.)

Hardman holds a B.A. in Philosophy and Religion from Appalachian State University and will graduate this Spring from Asbury Theological Seminary with an M.A. in Biblical Studies and an M.A. in Theological Studies. He blogs at www.thebarainitiative.com, is the father of two wonderful children, a church consultant for a mainline Christian publisher, and a freelance writer.

*******

In my previous blog, I outlined part of what it was like as a born and bred apologist, and I cautioned of a major problem with thinking so one dimensionally about faith. Apologetics can succeed in hiding doubt, fear, and faithlessness in any given person, as it did in me.

I played the game for so long that eventually I even wondered whether admitting to myself that I was just an “almost Christian” and getting things right was really worth the embarrassment of it all. As it turned out, it was—since obviously I am now writing this.

It took quite some time for me to admit that apologetics didn’t really save my faith but only gave me the impression that it did.

But, as I’ve stressed over and over, this denial was rooted in a particular way of thinking about Christianity which I think a lot of us evangelicals–especially those who have been captivated with apologetics–fall into: faith as science.

As the late Stan Grenz and John Franke note in their tremendous book Beyond Foundationalism: Shaping Theology in a Postmodern Context, it is somewhat ironic that modernist thinking has extended so far in both the directions of the “godless” and the “godly.” For every atheist that’s incorrigibly committed to the truth of his philosophical naturalism there is an evangelical incorrigibly committed to his theism in such a way that neither one lacks the need to feel absolutely certain.

For these evangelicals, conviction leaves no room for doubt, and so in popular Christian apologetics doubt is something to be assuaged with answers.

I think central to this view is the idea of inerrancy. It is a doctrine that seems to pervade even to the point of our trust in salvation. Indeed, I got an email yesterday from a junior in college asking “How can I trust the Bible if the Gospel of John has Jesus die on a Thursday?! If that’s false, might the whole thing be false too?!”

Her answer is the result of Christian thought being in bed with modernist thought, wherein one’s faith is not truly faith but, rather, certainty rested on shaky foundations. Remove too many bricks from that foundation and the whole thing tumbles down! Like this college junior, I myself bought into such a notion of faith and it rested mostly on the doctrine of inerrancy.

Of course, it’s a non sequitur to say “If Genesis is not science then Jesus didn’t rise from the dead,” but that doesn’t mean that that’s not the sort of bargain most people have adopted, probably unknowingly. But, as I’ll talk about in the next blog, there are major consequences to this way of thinking.

For the moment, I want to end on a positive note about what can happen when one begins to think outside of the inerrancy framework.

I remember my senior year of college taking the last undergraduate class I would ever take entitled “The History of Creation and Evolution.” The class was one of the best classes I ever took (and not once did I think the professor was an evil minion of Satan wanting to strip our faith from us!), for it challenged me to wrestle with a question that set off an authentic pursuit for truth and, more importantly, a relationship with Christ rooted in knowing more of him than about him.

The question was this: if evolution is right, does that make Christianity false? It was a bargain, for whatever reason, I was unwilling to accept. And it was only from that point forward that I saw a new way of wrestling with my questions. Of course, searching for answers would always be part of it. But I began to see faith and knowledge as centering on two different things.

Faith, while incorporating beliefs to an extent, is not about what you know and how well you are convinced of it. It is about how intimately you trust a person, and I can tell you from personal experience in some of the darkest moments in my life, it is only covenantal faith–not knowledge or arguments–that can appropriate doubt.

It is trust, not data, that allows one to wrestle through the night with God, through the unanswerable, and, indeed, the irrational. It allowed me to approach questions differently and it allowed me, a couple months later, to re-examine my own life and concede what was true: I didn’t know Christ as much as I knew about him.

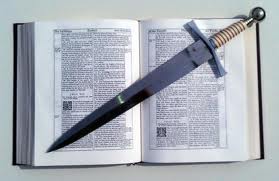

Since ridding myself of fear of reading Scripture outside of the inerrancy paradigm, I have returned to the Bible–not the systematic theologians or apologists–to answer the deepest questions, not needing to have the surface questions asked first.

In it I find beauty for God’s grace in allowing us to participate in its production, human error and all;

I find beauty in the multitude of voices, for the truth is sometimes life does seem nihilistic and we need Ecclesiastes to stand beside us or Job to yell at God with us;

I find beauty in reading Scripture primarily to save my soul and teach me how to live like and within Christ, not in teaching me what to believe and how to think about Christ.

At the end of it all, mere knowledge about God is about as useful to our lives as knowledge of plate tectonics. But certainly, if we strive to know him personally, to really develop a deep trust with him as “my Lord and my God” our knowledge about him will grow in tandum with our actual knowing of him.

When we rid ourselves of the need for an inerrant scientific like Bible, it has the ability to transform our faith from a need for certainty to a need for authenticity.