Sarah Kendzior received her PhD in anthropology this past May from Washington University in St. Louis. Earlier this week, she posted her reflections on the dim outlook of freshly minted PhDs, and I think she makes a number of sober observations. (I posted on this issue a while back here and here.)

Sarah Kendzior received her PhD in anthropology this past May from Washington University in St. Louis. Earlier this week, she posted her reflections on the dim outlook of freshly minted PhDs, and I think she makes a number of sober observations. (I posted on this issue a while back here and here.)

Highlights (or, as it were, lowlights):

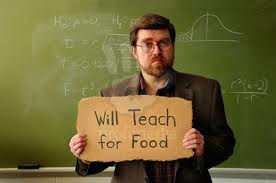

67% of American university faculty are part-time with contracts renewed on a semester by semester basis.

At an adjunct salary, a typical full time teaching load would net about $10,500 a year. (Kendzior is assuming $2100 a course for 5 courses, which is on the low end of a reasonable expectation. Let’s up this to 10 courses, a staggering amount of teaching: 4 each semester, one in January and 2 over the summer. At even $3000/course this yields $30,000/year with no benefits plus other potential drains on this salary like travel to multiple sites.)

Attending annual conferences to look for a full time job can cost about as much as adjuncting one course.

She notes the irony of conference organizers given preference to locales with “living wage ordinances.” Adjunct teaching is very time-consuming, leaving little time for a “second job” but the wage can be below the poverty line.

Teaching is considered a “calling” which is thought to justify a low wage. and expecting faculty to dip into savings in order to continue teaching.

And the money quote (and I’m sure Kendzior wishes I were being literal):

“In May 2012, I received my PhD, but I still do not know what to do with it. I struggle with the closed off nature of academic work, which I think should be accessible to everyone, but most of all I struggle with the limited opportunities in academia for Americans like me, people for whom education was once a path out of poverty, and not a way into it.“

I have heard some say that the use of adjuncts is a justice issue. Schools can get away with paying eager teachers a low wage while charging students high tuitions to be taught by adjuncts, all the while leading to life-long debt.

paying eager teachers a low wage while charging students high tuitions to be taught by adjuncts, all the while leading to life-long debt.

Let me crank out some numbers here to make sure you get good and depressed. Based on my own experience (and I’d be happy to hear others chime in), let’s allow $3000/course and 36 contact hours (3 hours a week for 12 weeks), that comes to about $83/hour. Not bad. But…

Let’s factor in class prep at 1 hour per class hour taught. (Experienced profs don’t need that much time, but most adjuncts are lower on the food chain.) Also, there is the intangible of needing to know your field in general and keeping up with some reading, which feeds into what you offer your students. Let’s put it at 3 hours a week (36 hours).

And let’s not forget grading exams and papers. It’s hard to quantify that because it depends entirely on the number and length of written assignments and whether texts are essays or fill in the circle. The number that seems right to me is about 20 hours at the end of the semester and another 20 throughout the semester (including midterms).

So, to teach one adjunct course at $3000 requires about 148 hours of work, or about $20/hour.

I want to remind you most adjuncts have earned doctorates. $20/hour. Hmm.

Anyway, 148 hours spread out over 12 weeks comes to about 12 hours a week. Which means–IF YOU CAN FIND THE WORK–you can probably squeeze in 5 courses a semester (a 50 hour work week) for a yearly salary of $30,000, maybe 7 courses if you have less prep time (although who teaches 7 course at a time!?). But now if you factor in travel time (since rarely do adjuncts work at only one school), travel expenses, the need for a social/family life, continued need for professional development (writing and speaking), and maybe a minute to yourself now and then, it begins to sound like you are in a pretty stupid line of work.

Who wins in this scenario? Are schools really doing right by the students and the teachers?

Personally, I think the answer is no, but we should resist the urge to demonize administrators for the simple fact that they are charged with keeping schools afloat financially. Money is driving all of this (duh) but that alone doesn’t make the situation unjust. The bigger problem is (stop me if you’ve heard this one) the rising cost of providing a college education that requires (1) new revenue steams, (2) increasing old revenue streams (tuition), (3) and lowering costs.

Cutting costs is always easier than increasing cashflow. An easy way to cut costs is to hire adjuncts. It costs about $75,000 to hire a low-level fulltime professor and maybe $100,000 or so for an experienced professor: about 2/3 to 3/4 to that is salary and the rest is health benefits, social security, etc. The teaching load is typically no more than 8 courses a year (and that’s high).

Why would a school shell out 75-100k to cover those 8 courses when it can be done for literally 1/4 to 1/3 the price? And when you have young men and women with earned doctorates from the most prestigious research universities in the country banging on the dean’s door to teach–anything remotely consistent with their field of training–it comes down to “simple economics”: get the job done as cheaply as possible.

Anyway, I’m depressing myself just writing this, but let me end with one more Puddleglum moment. True story. A friend of mine finished his PhD at a well-known research university. He landed a job at the seminary he had graduated from a few years earlier. At the same time, a maintenance man was hired at a competitive salary–which was considerably higher than the professor’s.

Anyway, I’m depressing myself just writing this, but let me end with one more Puddleglum moment. True story. A friend of mine finished his PhD at a well-known research university. He landed a job at the seminary he had graduated from a few years earlier. At the same time, a maintenance man was hired at a competitive salary–which was considerably higher than the professor’s.

When the department head approached the president, asking him how he can possibly justify paying a professor from an elite doctoral program considerably less than a maintenance worker, the president replied, “Because I can get a professor for that much. I can’t get a maintenance worker for that.”

I’m not sure you can fault the president. The problem is a larger systemic one. Unfortunately, I think this problem will wind up working itself out naturally and leaving a lot of collateral damage in its wake.