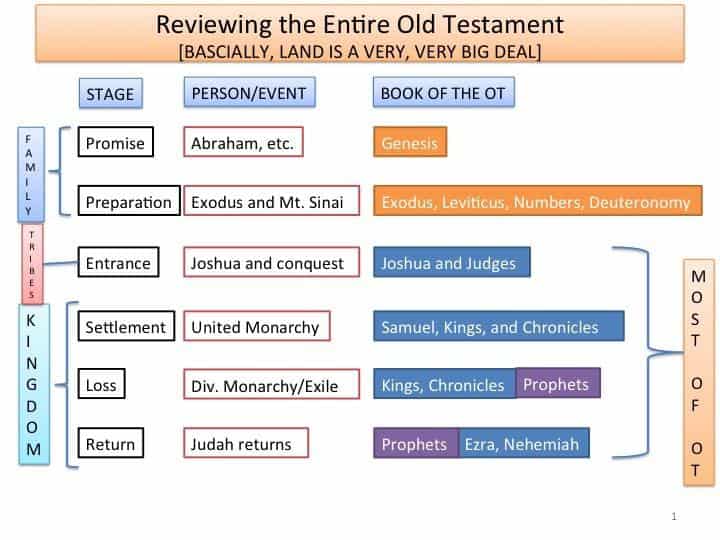

Did you know that, of the 39 books that make up the Christian Old Testament, all but 5 have something to do with Israel’s status vis-a-vis the land of Canaan?

Did you know that, of the 39 books that make up the Christian Old Testament, all but 5 have something to do with Israel’s status vis-a-vis the land of Canaan?

In other words, most of the Old Testament is about “land”—gaining possession of it and either staying in it or being exiled from it.

To anticipate some uptight comments, no I am not suggesting that land is the only or even the main theme of the Old Testament (I don’t think there is a “main” theme anyway). But I am saying that “land” is a great way of wrapping your arms around the Old Testament.

Here’s what I mean:

1. Genesis: the promise of land.

- Genesis is not just a bunch of stories about creation, and flood, and the earliest Israelites. It is very “land-conscious.”

- The first word out of God’s mouth to Abraham is the eventual possession of the Promised Land (Genesis 12).

- The Garden of Eden anticipates the Promised Land, and the story of Adam and Eve’s “exile” from Eden for disobedience mirrors Israel’s exile from Canaan for the same reason.

2. Genesis through Deuteronomy: preparation to enter the land

- The Pentateuch as a whole is set up to get readers to the entrance to the Promised Land. Israel’s story is about moving from one man, to a family, to tribes, to a nation freed from slavery, to meeting Yahweh on Mt Sinai in order to get to where they have been going since the call of Abraham: the land of Canaan. The Pentateuch prepares a people to take possession of the land.

3. Joshua and Judges: entering and securing the land

- What are these books about if not land, land, land, land, and land. That’s the whole point; “Phew, finally, we’re here. Let’s take the land we have long been promised by our God.”

4. United Monarchy: establishing a secure and permanent (one can only hope) presence in the land

- The story of the united monarchy (Saul, David, and Solomon) is about the realization and fulfillment of the promise to Abraham to have a permanent home in Canaan—as long as they obey, which leads us to . . .

5. Divided monarchy: the loss of land in two stages

- The exile of the northern kingdom in 722 BCE by the Assyrians and then of the southern nation of Judah by the Babylonians in 586 BCE must be seen for what it is: an undoing of where the storyline has been going since Abraham in Genesis 12: The children of Abraham no longer possess the land promised to Abraham.

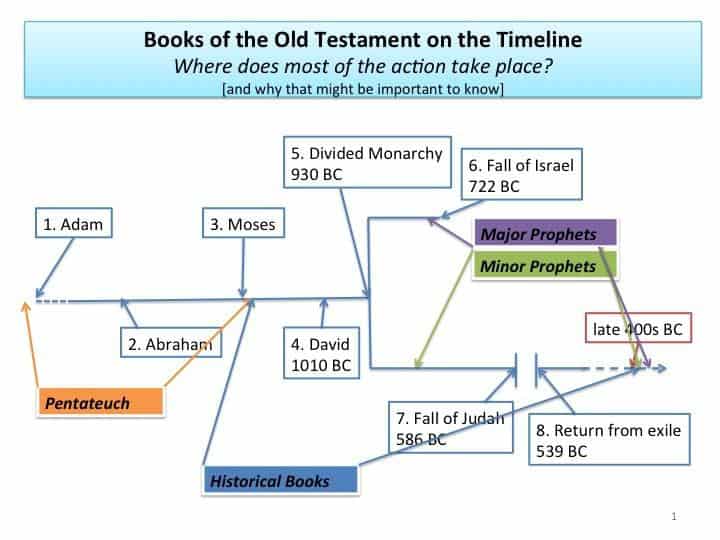

- It is also during this stage of the story that the biblical prophets begin to do their thing. Most of the major prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel) and the 12 minor prophets (Google it) deal with the Assyrian and Babylonian threats to the northern and southern nations and their stability in the land. Other prophets deal with the return to land (see below).

6. Judah’s return to the land

- This is the topic of Ezra and Nehemiah and of a number of prophets, most famously the prophet referred to in modern times as “Second Isaiah,” the anonymous prophet (or part of an Isaiah “school”) of Isaiah 40-55.

- It is during this time after the return from exile (the postexilic period) that the Old Testament begins to take the shape that we have today—and which is why the theme of land is so prominent in the Old Testament: the Judahites are telling their story of where they’ve been, how they got to where they are, and what their future holds.

Here is a slide that captures what I am getting at and that I make my students stare at for about 170 hours:

Here is another slide that, in very rough terms, plots the sections of the Old Testament canon onto a rough timeline (or maybe better, plot line) of the story of Israel from Adam to the return from exile.

So, of the 39 OT books, 5 are not directly relevant because they are not telling Israel’s story (Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs). The remaining 34 books have “land” written all over them:

- The Pentateuch is the ramp that gets the Israelites to the land, and

- The historical books and the prophets are all about what happens to them there—and a story of acquiring land, losing it, and returning to it.

I know that might not seem like the most thrilling way of looking at the Old Testament, but it does connect many of the dots. And it may begin to look more important if we remember that a sign—perhaps THE sign—of God’s blessings to Israel is their presence in the land. To be in the land is “life” and to leave it is “death” (e.g., Deuteronomy 3o:11-20; Ezekiel 37:1-14).

And as I end this I’m trying to tie it all into Christmas, but I can’t, other than to say Merry Christmas.

OK, I’ve avoided grading long enough. Back to it

[***For those interested, I explore all this a bit more, along with its implications, in The Bible Tells Me So (HarperOne 2014)***]