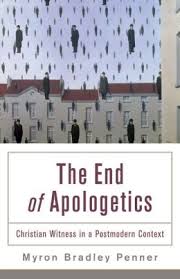

Today’s post is an interview with Myron Penner (PhD, University of Edinburgh), author of the upcoming The End of Apologetics: Christian Witness in a Postmodern Context

Today’s post is an interview with Myron Penner (PhD, University of Edinburgh), author of the upcoming The End of Apologetics: Christian Witness in a Postmodern Context, slated to be released July 1.

Penner is an Anglican priest in the Diocese of Edmonton, Alberta. He previously taught at Prairie College and Graduate School and served as a human development worker. He is the editor of Christianity and the Postmodern Turn: Six Views and coauthor of A New Kind of Conversation: Blogging Toward a Postmodern Faith.

Penner’s thesis is thoughtful and provocative. He argues that the modern apologetic enterprise is no longer valid, in that tends toward an unbiblical and unchristian form of Christian witness and does not have the ability to attest truthfully to Christ in our postmodern context. Christians to need change their well-entrenched but ineffective vocabulary and move toward a new way of conceiving the apologetic task, characterized by love and grounded in God’s revelation. (See fuller description on the publisher’s website.)

Q: To begin with, what sort of book is this and why did you write it?

I adopt what I call a “postmodern” perspective in this book, which I realize is a bit of a contentious place to start. But I mean something very specific by that. By postmodern I mean the awareness of the contingency or the problematic nature of the so-called modern project.

And I wrote the book because that’s where I am at. I no longer see how modern apologetics (and by that I mean the attempt to give reasons for Christian belief that are objective, universal, and neutral) is really all that helpful – for me or anyone else.

It began for me when I came across Søren Kierkegaard’s statement that whoever came up with the idea of defending Christianity in modernity is a second Judas who betrays the Christ under the guise of a friendly kiss; only, he adds, the apologist’s treachery (unlike Judas’s) is “the treason of stupidity.” At first this shocked and fascinated me. I wanted to try to understand what Kierkegaard meant by that, because it somehow sounded right to me. So I wrote the book.

Q: What would you say is the conceptual core of your book?

The key to my book lies in my assertion that modern reason – which I describe as objective, universal, and neutral – is something distinct from other conceptions of reason. It, therefore, is just one way of thinking about human reason, not the way. It is also a secular way to understand reason because we imagine it to be immune or separable from faith.

We usually just assume that what we believe counts as a good reason to believe something is natural, obvious, and the only way to think about it. But I find that assumption mistaken and deeply problematic. And ultimately, I believe that this way of thinking about reason is not the best way to be faithful to biblical faith. So I suggest that it is time to change paradigms.

I am therefore against apologetics insofar as it suggests – explicitly or implicitly – that what makes Christianity believable or worthy of our belief is that it is somehow grounded in human rational capabilities. There are all sorts of problems that come when we try to ground anything – but especially the Gospel – in the modern form of reason. And I try to spell out some of those problems in the book.

Q: When do you mean by saying you are “against“ apologetics?

It all hinges on Kierkegaard’s distinction between a genius and an apostle. Kierkegaard sees quite clearly that the modern form of authority for belief derives from genius – or what we might call “experts,” leaders in their fields. We believe what they tell us to believe because they know more than the rest of us they are more brilliant, intelligent, rational, insightful, etc.

Kierkegaard contrasts this with the Christian source of belief which comes from apostles, who differ from genius in that they do not ground their authority in their own talents or merits. Their message comes from God so the reasons they give are grounded differently than those of the genius.

We believe the Christian message is true, Kierkegaard says, not because it is brilliant or rationally grounded (in the modern sense), but because it is true, it comes from God. So I am really against the entire modern epistemological paradigm that produces modern apologetics, because it attempts to ground faith in genius or secular reason. The problem with modern apologetics is that, because it operates from the same (secular) grounds as modernity, it offers no real solution to modern issues.

Q: So, is apologetics always bad? Some people (e.g., university students) seem to be helped by apologetics when they go through periods of doubt. Can’t apologetics be used to bolster people’s faith? What would you say to someone who said that apologetics has really helped them in their Christian life?

No, I am against a specific way of thinking about faith – and really an entire way of imagining the world, including God, ourselves, and other people – not the act of responding to specific questions about Christian belief or practice. So I am not against what might be called “mere apologetics.”

I am not a fideist who thinks Christian belief negates or is against human reason, or that faith is opposed to any critical reflection on its beliefs whatsoever. I object to an exclusive emphasis on the modern form of reason because it empties faith of its Christian content and robs it of its authority. In this way Kierkegaard’s genius/apostle distinction suggests modern apologetics is itself a symptom of the nihilism (or meaninglessness) that is at the core of modern thought.

Modern apologetics is part of the modern paradigm. Thus, modern apologetics does nothing to help us cope with modern spiritual problems – it just perpetuates them.

So, if someone tells me they have been helped in their Christian life by apologetics, I say, “Wonderful!” But I would just like them to be very careful to distinguish this being helped by modern apologetics from it telling us the truth about God or ourselves or faith. I don’t think it necessarily does.

Q: But the discourse of Christian apologetics has a rich history prior to modernity, dating back to St. Paul in the New Testament and Justyn Martyr in the 2nd century, and running all the way up to St. Anselm (12th century) and St. Thomas (13th century). Are you saying that Christian apologists got it wrong through the centuries?

No, I am not against all apologetic discourse – just the kind that tries to imagine the foundations of Christian belief in terms of modern epistemology. As I suggested above, we continually forget or ignore or suppress the fact that the way we see the world and our assumptions about human reason and the way it relates to faith is just one way to think about those things.

Ancient and medieval Christian apologists thought of the world and God and human reason in very different ways than we do. They literally could not imagine that our reasons for believing things conform to the dictates of modern secular reason. When, for example, medieval theologians engage in “natural theology” (arguments for God’s existence) they do so from within a specific set of assumptions, practices, and beliefs of a community of faith.

Q: In the book, you talk about “apologetic violence.” What do you mean by that?

Well, two things, really. First, apologetic violence happens at the personal level when apologetic arguments are used to treat people badly. Arguments don’t just “prove.” They may perform a wide variety of functions and can be used to do a lot more than advance a conclusion. When they are used to demean, ridicule, show-up, or hurt another person in any way, I call that a form of violence.

Second, apologetic violence can also happen at the social level when Christian apologetic practice merely reinforces and defends a given set of power relations operative within an unjust social structure. We then overlook real people and proclaim to them the “truths” of the gospel packaged in “universal” concepts and categories (as well as practices) to which they cannot relate in any personal way and which have often played some role in their mistreatment or exploitation.

An apologetic argument for Christian truths in those situations will be received as an implicit justification for the wrong that has been done the established powers. This is perhaps an even more insidious form of apologetic violence because it is generally invisible. It permeates our everyday practices and beliefs, and lurks just below the surface.

The point I want to make about apologetic violence is that when it happens at one or both of the above levels, then it is not the Gospel that is being defended or advanced.

Q: Explain what you mean in your last chapter about “The Politics of Witness.”

Following up on the second kind of apologetic violence – the social kind – it becomes possible to see how Christian witness (and apologetics) is also political.

The kind of politics operative here is what I call a deep politics, however, for I am not talking about leveraging power within some structure of governance. I am speaking at a more profound level of the relations that exist between persons that constitute them as a people—the level at which values and purposes give rise to explicit political structures that govern the relations between persons and how they conduct their common life together. Deep politics concerns public power and power relations between private persons.

So when I say the Christian witness is political, I mean the concern about ideological or systemic apologetic violence connects Christian witness to the issues of deep politics. Against modern apologetics, a postmodern prophetic witness acknowledges that there is no space outside political power in which we can persuade people. The deep politics of modernity allows modern apologetics to imagine itself as operating apolitically, as dealing only with the rational justifications.