Mark S. Smith’s book The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel opens with a quotation from the 6th c. AD writer on Roman antiquity, Lydus.

There has been and is much disagreement among theologians about the god honored among the Hebrews (De mensibus 4.53)

Indeed.

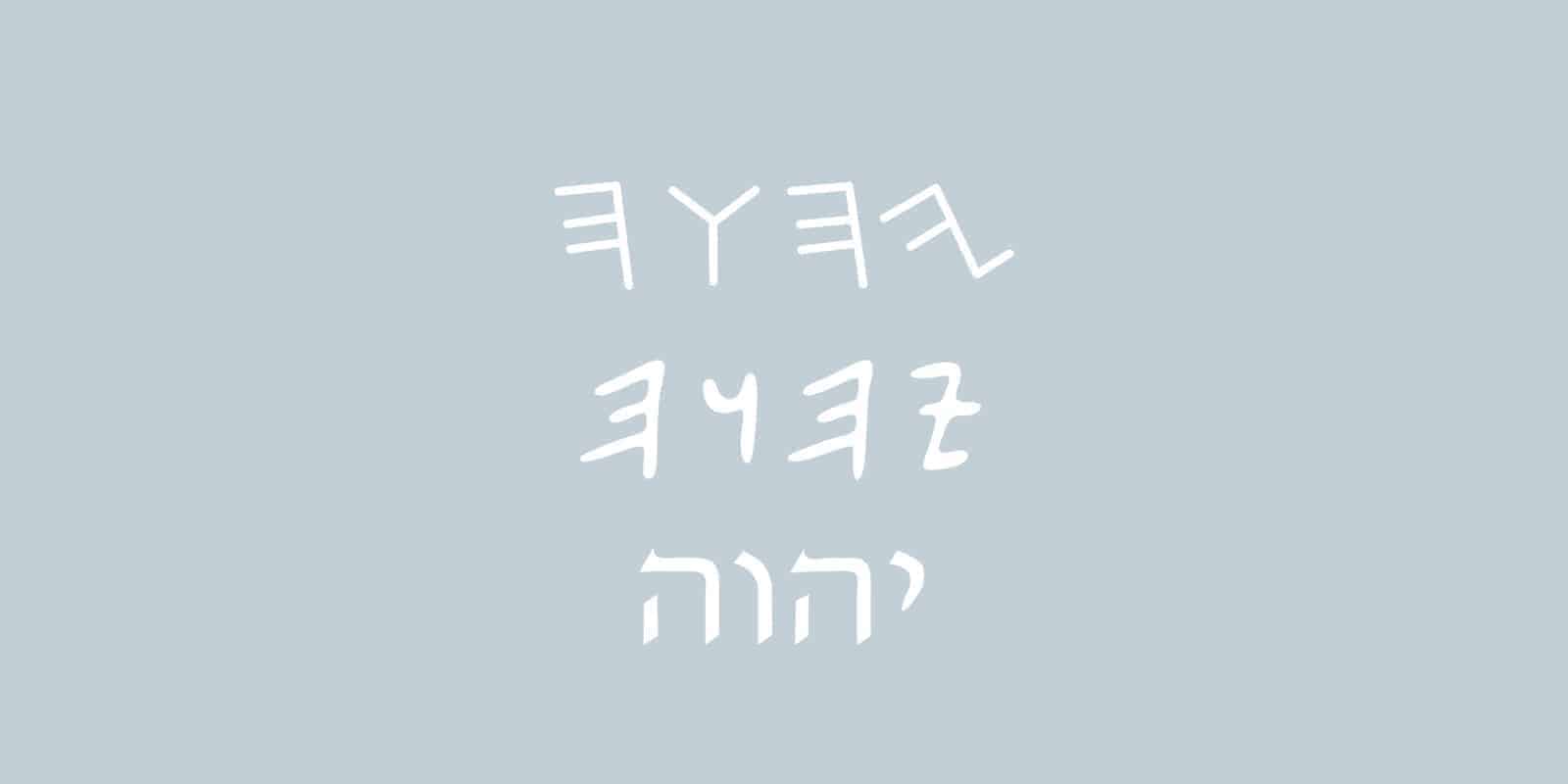

For the next 200 pages, Smith looks at the “role of Yahweh within Israelite religion” vis-a-vis older Canaanite deities like El, Baal, and Asherah (also known to us from the Bible).

Ferreting out how the ancient Israelites came to worship Yahweh and what that meant in the context of ancient polytheistic cultures has been a huge topic ever since modern biblical scholars/archaeologists began learning new things about (1) ancient Israel and (2) ancient polytheistic cultures.

The bottom line, mainstream view—I shudder even to attempt to summarize it in one sentence—is that the Hebrew scriptures contain a record of Israel’s diverse and changing views concerning God, where the experience of the Babylonian Exile was a major turning point in the emergence of monotheism (the belief that only one God exists) out of monolatry (many gods exist but only Yahweh is worthy of worship).

God, in other words, has a history—or at least on the pages of the Old Testament. We are seeing development over time in how God was understood.

This mainstream view does not rest well with the biblical progression of events, namely: Israel knew Yahweh as the/their only God from the time of Abraham, and how well they did as a people/nation depended on remembering that and worshiping/obeying Yahweh alone.

For biblical scholars of the last century or so, this picture is complicated by

(1) the Bible’s own hints and nods at a more complicated “early history of God” (hence Smith’s book), and

(2) our considerable and growing understanding of religion in general in the ancient Near East, especially Canaanite and Ugaritic religion, which are closest to Israelite religion.

I’m used to this sort of thing, but I know many are not. That’s fine. The point, though, is that the modern study of the Old Testament has irrevocably affected what we can expect from the Bible in terms of “brute information” about God.

The modern study of the Old Testament doesn’t tell you what to believe, like a bully, but it has placed the Old Testament firmly in its culture moments—so firmly, in fact, that a well rounded view can’t just make believe the last hundred or so years of thinking on this subject didn’t happen.

Here’s my take-away from all this—and I’m asking you (or at least humor me) to believe me when I say that this is not a last minute frenzied punt from my own end zone before the sack. My life, such as it is, is about synthesizing my own spiritual life with what I’ve been trained to do and what I do for a living, which is to say I’ve thought about this a good bit and hang out with others who have done the same.

Studying the Bible and Israel’s past is a regular reminder to me that my ultimate object of trust is God, not the Bible (or how I understand the Bible). That’s not knocking the Bible. It’s acknowledging that the Bible—even where it talks about God—is a relentlessly contextual collection of ancient literature that takes wisdom and patience to handle well, and in doing so drives us toward further contemplation of God here and now.

God is bigger than the Bible.

I see Jesus and Paul already sounding that note when they began reshaping traditional expectations of God.

I haven’t come to this place quickly or casually, though from my vantage point today, it feels rather commonsensical to me—though I don’t impose that on anyone, at least not until I gain supreme, ultimate power, which is the plan.

One last point, to anticipate a common response: “But how can you know anything about God other than what the Bible tells you?” Fair question, but that potential problem does not dismiss the observation about God in the Bible. When you get close to the Bible, prepare to have your view of the Bible reoriented. The irony is that it is the study of the Bible that has led me down this path.

And it’s a nice path, at least for me. God is more outside of my control this way, which I can’t help but think is as it should be. As Lydus said over 1400 years ago, Yahweh isn’t easy to get your arms around—for Israelites or for those who have followed in their footsteps.

You can listen to my podcast on this topic HERE. You can read more about the nature of the Bible and Christian faith in The Bible Tells Me So (HarperOne, 2014) and Inspiration and Incarnation (Baker 2005/2015).