Today is the second of six posts by Karl Giberson, noted speaker and writer about the intersection of Christian faith and science (see the first post here). Giberson is blogging on his new book The Wonder of the Universe: Hints of God in a Fine-Tuned World (IVP). The series includes 6 excerpts from the book: the opening and closing sections of the book, and 4 representative samples from the rest.

Today is the second of six posts by Karl Giberson, noted speaker and writer about the intersection of Christian faith and science (see the first post here). Giberson is blogging on his new book The Wonder of the Universe: Hints of God in a Fine-Tuned World (IVP). The series includes 6 excerpts from the book: the opening and closing sections of the book, and 4 representative samples from the rest.

Giberson is the author of several books on the subject, including Saving Darwin: How to Be a Christian and Believe in Evolution, The Language of Science: Straight Answers to Genuine Questions(with Francis Collins), and The Anointed: Evangelical Truth in a Secular Age (with Randall J. Stephens). Giberson is also co-founder of BioLogos, along with Francis Collins and current president Darrell Falk. (See his complete bio here.)

Be a Christian and Believe in Evolution, The Language of Science: Straight Answers to Genuine Questions(with Francis Collins), and The Anointed: Evangelical Truth in a Secular Age (with Randall J. Stephens). Giberson is also co-founder of BioLogos, along with Francis Collins and current president Darrell Falk. (See his complete bio here.)

Today, Giberson continues the story of how science brought British philosopher Antony Flew from atheism to theism. Science helped him see that the cosmos was not accident but created.

Excerpt #2: The Heavenly Declaration

“The heavens,” wrote the psalmist “declare the glory of God” (Ps 19:1 NIV)

“The heavens,” wrote the psalmist “declare the glory of God” (Ps 19:1 NIV)

The universe that inspired the psalmist three thousand years ago grows grander as each new generation of astronomers adds yet another layer of understanding. Each new discovery pushes back the boundary that separates the known universe from the vast terra incognita that beckons and teases us to keep going, to sail ever further from familiar shores.

A few centuries ago the great philosopher Immanuel Kant repeated the Psalmist’s declaration:

Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the more often and steadily reflection is occupied with them: the starry heaven above me and the moral law within me. Neither of them need I seek and merely suspect as if shrouded in obscurity or rapture beyond my own horizon; I see them before me and connect them immediately with my existence.

The night sky still beckons us, as it once did the psalmist. I spend time each summer at a rustic family cottage in the wilderness of my native New Brunswick, Canada. There, miles from electricity, the night sky does not compete with artificial light. Smog does not obscure it. Planes do not draw white trails on it. It does not compete with cable television or even cell phones, silenced by the absence of signals. The night sky is simply there, quietly declaring the glory of God. Its many lights reflect off the ripples of the lake, and are accompanied by the rustling of leaves and the voices of the many creatures that call this wilderness home. Only a jaded soul could sit by that lake and not wonder if there wasn’t some larger meaning to the experience.

I can see what the psalmist saw and rejoiced as he did. But I watch the night sky through the eyes of a twenty-first century scientist. I have the benefit of centuries of scientific advancement and can see, in my mind’s eye, so much more. Those visible stars are just the advance guard of an almost infinite army of stars going back almost forever. The stars are not attached to a dome that one might reach with an ambitiously tall tower or puncture with a long-range missile. They are so far away that their light has been traveling at unimaginable speed for years, centuries, millennia and longer.

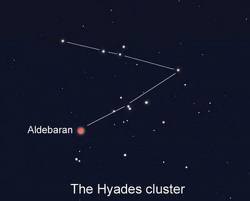

The light from the stars in the Hyades Cluster began its journey to the earth at about the time that my ancestors— Loyalists from Pennsylvania—began their journey to this part of North America in the eighteenth century. The light from the closest stars, the trio that make up Alpha Centauri, takes over four years to reach earth. The most distant star ever detected from the earth is a “gamma ray burster” that launched its signal almost 13 billion years ago, when the universe was young. The powerful gamma ray signal from this star began its journey before our planet was even formed, reaching the earth in April 2009.

Loyalists from Pennsylvania—began their journey to this part of North America in the eighteenth century. The light from the closest stars, the trio that make up Alpha Centauri, takes over four years to reach earth. The most distant star ever detected from the earth is a “gamma ray burster” that launched its signal almost 13 billion years ago, when the universe was young. The powerful gamma ray signal from this star began its journey before our planet was even formed, reaching the earth in April 2009.

The psalmist did not know that the stars were made of hydrogen and helium. He did not know they generated their energy through nuclear fusion or that many of them explode at the end of their lives. He knew nothing of galaxies and the layers of structure in the cosmos. He did not understand how fast light travels or that the light from our sun powers photosynthesis and many other processes here on the earth.

The universe brought into view by science is like a collection of Russian matryoshka dolls nestled one inside the other. With the psalmist we can see the outer layer—and it is grand. But inside are additional layers, each one with a new type of grandeur. And at the very end of the unpacking lie the remarkable laws of physics that keep the earth orbiting about the sun, the sun shining reliably, and the sunlight providing energy to sustain life on our planet.

The universe as we understand it today inspires awe. And for those open to its message—from the psalmists of yesteryear to the believers and even the thoughtful skeptics of today—it speaks of a Creator. Our universe does not look like a cosmic accident, where lots of stuff just happened. It looks like the expression of a grand plan—a cosmic architecture capable of both supporting life such as ours and of inspiring observers like us to seek out the Creator.

This is why Antony Flew—“world’s most notorious atheist”—changed his mind and started believing in God.

Next post: “Excerpt #3: The Wonder of Water”