Here’s what I think about something and I don’t care if you think I’m wrong.

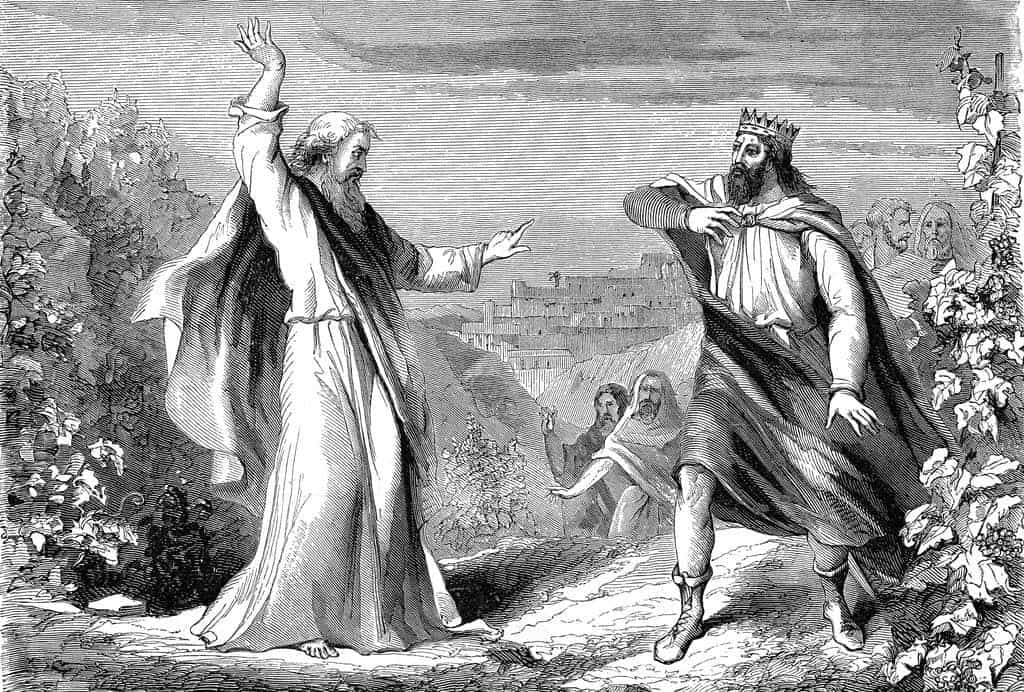

One of the things that I find fascinating about the Old Testament is how the power of the king was kept in check (at least theoretically). A king’s word wasn’t automatically law. A king’s will was not automatically the will of God. Rather, a king was held to a standard higher than and outside of himself.

That external standard is two-fold: the covenant stipulations given to Moses (Torah) and the word of the prophets.

Concerning Torah, it gets a bit tricky, because the most explicit reference to the king’s subjection to Torah is in Deuteronomy 17, though presented as the words of Moses (as is the rest of Deuteronomy), probably reflects a later situation—namely the late 7th century and the time of King Josiah.

But still, I don’t think that the idea of the covenant made by God with the people through Moses was a new idea in the 7th century, but rather was part of Israel’s self-understanding for much longer that gets “codified” later.

Concerning the prophets, they weren’t predictors of a far distant future time, but conduits for the will of God for very present problems, often focused on the abuse of power by kings or priests. So think of the prophets as part of this check on power.

What’s tricky here is that the prophets rarely (ever?) appeal to the Torah for support when calling kings to account—which is one reason why modern biblical scholars have tended to argue that Torah is later than the prophetic word.

There’s a lot of truth to that—not there there were no “standards of law” before the onset of the prophetic voice, but only that there was no one officially sanctioned chapter-and-verse body of laws for the prophets to appeal to. The prophets who spoke during Israel’s monarchy had no Torah in the sense in which we know it.

Anyhoo, we won’t get into all that here. I just think it’s interesting and vitally practical in this day and age to think of the Torah from this perspective—as a means of holding power in check, especially if we bring the Jesus angle into it (as mediated through Paul and the book of Revelation).

At least part of what it means for Jesus to be the super-fulfillment of Torah and the prophetic role is his ultimate rule over all rulers, all political regimes—a point made at great length in the book of Revelation. The Gospel, in other words, is the standard by which the rulers are judged. Not so much on the level of personal piety but on the level of how their rule and their actions affect people.

Those who follow Jesus have an obligation to voice their opposition to corrupt rule, and to never allow the Kingdom of God to become enmeshed with political agendas.

Like the prophets of old, we have the obligation to be sure that justice, peace, and righteousness remain the higher standard by which the state is held accountable rather than aiding and abetting the state to redefine and co-opt that standard.