Here is my definition of “biblicism.”

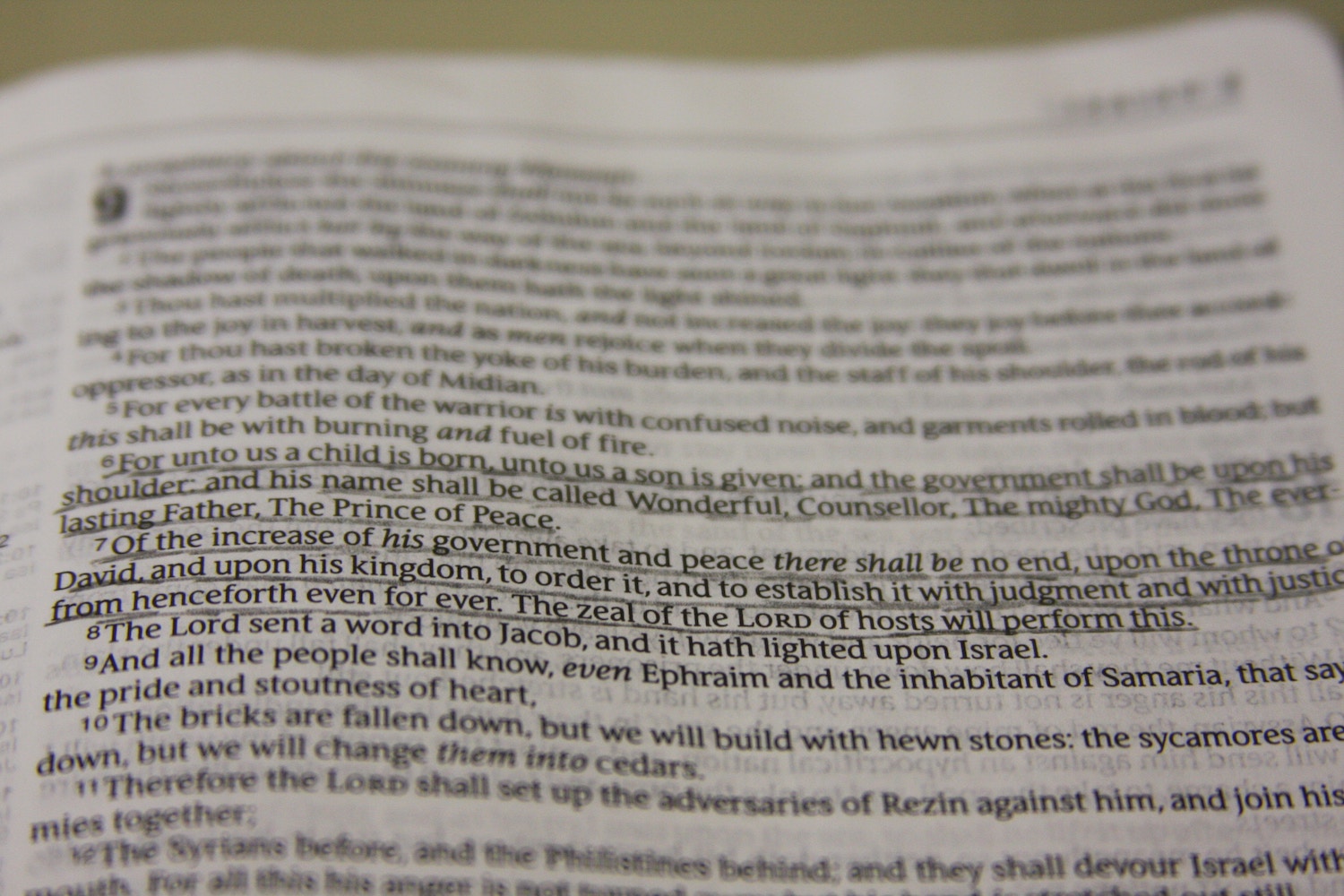

Biblicism is the tendency to appeal to individual biblical verses, or collections of (apparently) uniform verses from various parts of the Bible, to give the appearance of clear, authoritative, and final resolutions to what are in fact complex interpretive and theological issues generated by the fact that we have a complex and diverse Bible.

Put another way, biblicism is a tendency to prooftext—where the “plain sense” of verses are put forth as final and incontrovertible “proof” of a given theological position.

In The Bible Tells Me So, when I talk about a “rule book” or “owner’s manual” way of reading the Bible, I’m talking about biblicism.

If I may be clear on something, I am not saying that the Bible doesn’t shape, give guidance, and/or directives for matters of faith and life. I am saying that discerning how the Bible does that is more than lifting verses from the Bible and laying them out on the table.

The Bible simply doesn’t work that way.

That’s because the Bible was written by different people, under different circumstances, for different reasons, spanning more than a thousand years. It was written during times of peace and war, in safety and exile, in Israel’s youth and chastened adulthood, and then under Roman occupation. Its writers were priests, scribes, kings, and simple folk, separated by time, politics, and geography, not to mention Myers-Briggs personality types.

Any claim to what the Bible “teaches” us has to go beyond citing a lone verse or amassing several verses and move toward a deeper engagement with:

- The immediate literary/theological context of the verse(s).

- The place of any verse(s) in the context of the biblical grand narrative (the “canonical context”).

- The self-evident and theologically vital diversity, differences, and various transformations that we see throughout the Bible.

- The various ancient contexts out of which any and all biblical utterances arise.

These 4 are related and play off of each other. For example: 4 is at least one of the reasons why we have 3; the fact that we have 3 alerts us that we need to keep in mind 2.

These 4 issues are not steps to follow that insure proper interpretation. They do not end hermeneutical conversations; they allow them to happen.

I can’t think of a single point of theology or Christian doctrine that can keep these 4 factors at a distance and still maintain hermeneutical, theological, and doctrinal integrity.

But biblicism:

- is often a power move, a rhetorical bullying tactic for claiming God’s support for our ideas,

- relieves us of the responsibility of respecting the Bible enough to struggle with it and what it means to read it well—which is what Jews and Christians have been doing for over 2,500 years,

- sells the Bible short by taking the easy way out of reading the Bible like it’s a phone book or line-by-line instructional manual, rather than what it is: a complex, diverse, intermingling of wise reflections on life with God, written by the faithful for the faithful.

Biblicism isn’t biblical—and I’m happy to allow the apparent contradiction of that statement to stand as is.

[Comments are moderated and may take as long as 24 hours to appear. And that’s not a long time at all in the grand scheme of life, now is it?]