Today we have part 3 of a 4-part series by Michael Hardin, “How Jesus Read His Bible.” Hardin (see full bio at part 1) is the co-founder and Executive Director of Preaching Peace a non-profit based in Lancaster, PA whose motto is “Educating the Church in Jesus’ Vision of Peace.” Hardin has published over a dozen articles on the mimetic theory of René Girard in addition to essays on theology, spirituality, and practical theology. He is also the author of several books, including the acclaimed The Jesus Driven Life

Today we have part 3 of a 4-part series by Michael Hardin, “How Jesus Read His Bible.” Hardin (see full bio at part 1) is the co-founder and Executive Director of Preaching Peace a non-profit based in Lancaster, PA whose motto is “Educating the Church in Jesus’ Vision of Peace.” Hardin has published over a dozen articles on the mimetic theory of René Girard in addition to essays on theology, spirituality, and practical theology. He is also the author of several books, including the acclaimed The Jesus Driven Life from which these posts are adapted.

In today’s post, Hardin continues his discussion of Jesus’s use of the Old Testament. Hardin argues that the manner in which Jesus quotes his scripture shows us the God Jesus proclaims is not retributive. And, as you’ll see, John the Baptist was confused about this (as you might be).

**********

We ended the last post by saying,

Nothing irks some folks more than losing a God who is wrathful, angry, retributive and punishing. This is only because we want so much to believe that God takes sides, and that side is inevitably our side.

So much of Jesus’s teaching subverts this sacrificial way of thinking.

One example is the parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector found in Luke 18:9-14, where what counts as righteousness is completely and totally turned on its head!

If, in fact, as I argued in my last post, that Jesus begins his ministry by asking what God without retribution looks like (Luke 4), and if he acts this way in his ministry, and if he interprets his Bible to say such things, the question arises:

- Shouldn’t we also follow Jesus in interpreting our Bibles in the same way?

- Is biblical interpretation also a part of discipleship?

- Does following Jesus include more than just living a virtuous life?

- Might it also have to do with helping folks change the way they envision God?

Such was the case for Jesus who called people constantly to “change your thinking.” This is what repentance is, changing the way you think about things (Greek metanoia). When we change the way we see and understand the character of God, everything else changes and we turn back (Hebrew shuv) to the living and true God.

Such was the case for Jesus who called people constantly to “change your thinking.” This is what repentance is, changing the way you think about things (Greek metanoia). When we change the way we see and understand the character of God, everything else changes and we turn back (Hebrew shuv) to the living and true God.

We can see Jesus doing the same thing in Luke 7:18-23 when he responds to the followers of John the Baptist. Herod had imprisoned the Baptist for his preaching against the Herodian family system. John did not want to die without knowing whether Jesus was the one to come.

Now what could possibly have created this doubt in John’s mind? The answer comes in Jesus’ response to John’s followers. “Go and tell John what you have seen and heard,” Jesus says and then follows a list of miracles. Is Jesus saying, “Tell John you have seen a miracle worker and that God is doing great things through me?”

Doesn’t John already know these things about Jesus? Surely he does. Healers were rare but they were not uncommon in Jesus’ day. What then is Jesus really saying?

Luke 7:22ff is a selection of texts, mostly from Isaiah but also including the miracles of Elijah and Elisha (blind, Isaiah 61:1-2, 29:18, 35:5; lame, 35:6; deaf, 29:18, 35:5; poor 29:19; dead/lepers, I Kings 17:17-24 and 2 Kings 5:1-27).

The Isaiah texts all include a consequent or subsequent reference to the vengeance of God none of which Jesus quotes. As in Luke 4 what is at stake is the retributive violence of God that was an important aspect of John’s proclamation (Luke 3:7-9).

John, like the prophets before him, believed that God was going to bring an apocalyptic wrath. Nowhere in Jesus’ preaching do we find such and this is what confused John, just as it confused Jesus’ synagogue hearers.

Jesus implicitly tells John, through his message to John’s followers, that the wrath of God is not part of his message, rather healing and good news is. That is, Jesus is inviting John to read Isaiah the way he did!

The last thing Jesus tells John the Baptists’ disciples is “Blessed is the person who is not scandalized on account of me?” What could have caused this scandal? What had Jesus said and done that would cause people to stumble on his message? The clues are here in both Luke 4 and 7.

Jesus did not include as part of his message the idea that God would pour out wrath on Israel’s enemies in order to deliver Israel. Violence is not part of the divine economy for Jesus.

Sad to say, most Christians still think more like John the Baptist than Jesus.

Christians have lived a long time with a God who is retributive.

- We say that God is perfect and thus has the right to punish those whom he deems fit.

- We say that God will bring his righteous wrath upon all those who reject God.

- We say that God can do what God wants because God is God.

All of this logic is foreign to the gospel teaching of Jesus about the character of his heavenly abba.

Jesus does not begin with an abstract notion of God or Platonic metaphysics, but with the Creator God whom he knows as loving, nurturing and caring for all persons regardless of their moral condition, their politics, their ethnic background or their social or economic status. God cares for everyone equally and alike.

nurturing and caring for all persons regardless of their moral condition, their politics, their ethnic background or their social or economic status. God cares for everyone equally and alike.

By removing retribution from the work and character of God, Jesus, for the first time in human history, opened up a new way, a path, which he also invites us to travel.

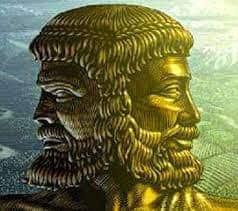

Sadly few have found that this path and church history is replete with hundreds, even thousands of examples of a Janus-faced god, a god who is merciful and wrathful, loving and punishing. Some have said that we need to hold to both of these sides together.

Jesus didn’t and neither should we. It is time for us to follow Jesus in reconsidering what divinity without retribution looks like.