This past weekend I took part in a conference at St. Thomas’s Episcopal Church in Whitemarsh, PA, sponsered by St. Thomas and the Center for Biblical Studies and by a generous gift from the Philadelphia Theological Insitute.

This past weekend I took part in a conference at St. Thomas’s Episcopal Church in Whitemarsh, PA, sponsered by St. Thomas and the Center for Biblical Studies and by a generous gift from the Philadelphia Theological Insitute.

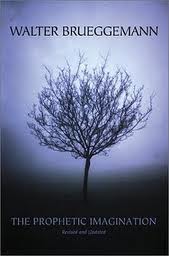

The conference was on Making Sense of the Old Testament. The main speaker was Old Testament theologian Walter Brueggemann, author of, as of this weekend, 58 books (though who knows what he did on the plane ride home–ha ha). He is perhaps best know for The Prophetic Imagination and his Theology of the Old Testament. Brueggeman gave five substantive talks ranging from the nature of the Old Testament as a whole to the prophetic role of truth-telling and hope-telling.

Carolyn Sharpe from Yale Divinity School gave two talks, one on irony in the Old Testament and the other on the Psalms 44 and 46 and spiritual transformation. Sharpe also teaches a course at Yale on Brueggemann’s theology.

I was there as a respondent to both speakers, offering alternate points of view on some very controversial subjects, as well as connecting some of the ideas we heard to the New Testament.

If you have ever heard Brueggemann speak or preach, you will already know that his enthusiasm and passion for Old Testament theology is contagious. He is a riveting teacher and bids his audience to enter into his own narrative of what the Old Testament is about and how it is to be “performed” in today’s world.

I took pages of notes, and I thought I’d give a sketch only three of the more salient points he made over the weekend, and that I know I will take with me.

The heart of the Bible is not the presentation of history but a font of imagination that hosts a world other than the one in front of us. By “imagination” Brueggemann does not mean “irreal” but quite the opposite. He claims that the world we live in, the world where the empires of man rule, is the parody. All empires are acts of imagination: they present a world that lures humanity into its false hopes and lays claim to our hearts and souls as the unquestioned status quo.

front of us. By “imagination” Brueggemann does not mean “irreal” but quite the opposite. He claims that the world we live in, the world where the empires of man rule, is the parody. All empires are acts of imagination: they present a world that lures humanity into its false hopes and lays claim to our hearts and souls as the unquestioned status quo.

Before you know it, you are duped. You take what the world offers–commodities, prejudices, fears, injustices, violence, false gods–and you accept it all as a given.

To this tired life, accepted as unquestioned reality, scripture offers another world, another way of being, that is both unsettling and comforting as it stands in prophetic judgment over the empires of the world. Scripture, in other words, is counter-imagination, a “rival eschatology,” as N. T. Wright puts it, to any system that claims “we have now arrived.” Empires do not like the promise of scripture because promise implies the the present is inadequate. Counter-imagination makes empires nervous.

Scripture itself demonstrates the clash of empires. Israel’s deliverance from Egypt takes the Israelites from a world of slavery to Pharaoh, where all they do is never enough and they are enslaved to producing “banks” (storehouses) where the king of that empire can keep his excess wealth. God delivers Israel to a world where their God is not a task master but a deliverer and where their world is not defined by “commodities” but by “fidelities” (i.e., the covenant).

The God of Scripture is not the “omni” god of the Enlightenment (omnipotent, omnipresent, omniscient) or of nineteenth century higher criticism (to which both liberals and fundamentalists ironically bow), but a God who is embedded as a character in narrative, the subject of active verbs, the God who is on your side and fights for you. Brueggemann finds both the pre-critical (literalistic reading of scripture) and critical (dis-integration of scripture) spiritually unhealthy. The former is naive and the latter is suspicious of scripture. A post-critical attitude is a way forward that retrieves pre-critical devotion in conversation with true critical insights.

For example, he argues that the prophetic corpus was assembled to speak to the realities of the exile (a critical insight of the last two centuries), which helps us today see the urgency of speaking God’s word into analogous situations. He referred to 587 BC (when the exile began) as the “9/11 of the Old Testament,” meaning the moment when Israel became utterly disoriented, for “such a thing should not happen.” Likewise, Good Friday is the 9/11 of the New Testament, for a crucified King of the Jews, a slain Messiah, is unthinkable.

Both events, though utterly disorienting, are transformative events that further God’s purposes in the world. Against all expectations, God was on the move in both cases, and delivered a blow against the claims of false empires to define how God is supposed to appear (comfortably in support of empire).

Prophets are truth-tellers and the hope-tellers. The role of biblical prophets is to deconstruct the world of power through poetic rhetoric. Power structures are in a state of denial, meaning they hold on to power at all costs. By his truth-telling poetic critique, the prophet introduces despair to the halls of power and to those who place their hope in them. Once such despair is fully embraced and lamented, the prophet declares a word of hope, envisioning a time when God will bring something utterly new and counterintuitive out of despair.

This stuff preaches, and the line between preaching and teaching was thin indeed for Brueggemann.

Brueggemann also talked about Exodus, divine violence, and a few other smaller topics. I hope to blog about them as well in the coming days. In the meantime, tells us what you think about these ideas, especially if you are familiar with Brueggemann’s writings.

Brueggemann also talked about Exodus, divine violence, and a few other smaller topics. I hope to blog about them as well in the coming days. In the meantime, tells us what you think about these ideas, especially if you are familiar with Brueggemann’s writings.