Today’s post is an interview with Jonathan D. Fitzgerald, author of Not Your Mother’s Morals: How the New Sincerity is Changing Pop Culture for the Better. Fitzgerald is a writer and educator whose with a keen interest in how religion shows up in culture. He is an editor at Patrolmag.co and writes a weekly column for the popular religion website Patheos. His freelance works has appeared in such places as The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The Daily Beast, Christianity Today, Religion Dispatches, The Huffington Post, Killing the Buddha, and The Jersey City Independent.

Today’s post is an interview with Jonathan D. Fitzgerald, author of Not Your Mother’s Morals: How the New Sincerity is Changing Pop Culture for the Better. Fitzgerald is a writer and educator whose with a keen interest in how religion shows up in culture. He is an editor at Patrolmag.co and writes a weekly column for the popular religion website Patheos. His freelance works has appeared in such places as The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The Daily Beast, Christianity Today, Religion Dispatches, The Huffington Post, Killing the Buddha, and The Jersey City Independent.

In Not Your Mother’s Morals, Fitzgerald argues that today’s popular music, movies, TV shows, and books are–you may want to sit down for this–making the world a better place. For all the hand-wringing about the decline of morals and the cheapening of culture in our time, contemporary media brims with examples of fascinating and innovative art that promote positive and uplifting moral messages–without coming across as “preachy.”

The catch? Today’s moral messages can be quite different than the ones your mother taught you. Fitzgerald compares the pop culture of yesterday with that of today and finds that while both are committed to major ideals—especially God, Family, and Country—the nature of those commitments has shifted.

1. What clued you in to the possibility of moral stories in popular culture, of all places?

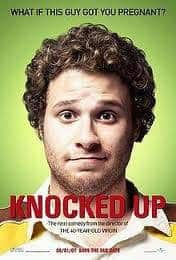

I guess it was back in 2007, I came across two examples that I’d eventually use to support my thesis. They were vastly different artifacts: David Foster Wallace’s collection of essays titled Consider the Lobster and the film “Knocked Up,” written and directed by Judd Apatow. What these two things have in common is that they are unlikely places to find moral stories, and yet there they were.

So in these, and so many other places throughout pop culture in recent years, I realized that writers, musicians, and film makers were telling moral stories through their art.

2. What’s the deal with the title? Why Not Your Mother’s Morals?

The operating premise here is that though there are all these amazing portrayals of moral stories in pop culture, many people my of parents’ generation would never really see them. They wouldn’t get through “Knocked Up,” which I failed to mention is also a very crass movie. And, I think this is in part what allows Apatow to tell a moral story to a contemporary audience.

culture, many people my of parents’ generation would never really see them. They wouldn’t get through “Knocked Up,” which I failed to mention is also a very crass movie. And, I think this is in part what allows Apatow to tell a moral story to a contemporary audience.

But then, from there, it seemed clear that even some of the moral concerns that are raised, like environmentalism, bullying, and marriage equality, wouldn’t even register to older generations as moral concerns. Or, if they did, they wouldn’t come out on the same side as pop culture seems to.

3. Tell us what this “New Sincerity” thing is all about.

While it’s difficult (impossible?) to capture the ethos of an entire age, many people who look at young adults today, and the cultural artifacts they consume, have come to the conclusion that we live in an age wherein the values of sincerity and authenticity are among the most significant virtues. This probably got its start in the 1980s and has been picking up pace ever since as a response to decades in which cynicism and a detached posture dominated.

In the book, I explain how the New Sincerity created a space for artists to explore moral questions in their art without fear of ridicule or recourse.

4. What do you hope readers will come away with after reading your book?

My point here is really to bring attention to the New Sincerity movement and to highlight the positive effect it is having on popular culture. I’m under no illusions that any pop culture moment is sustainable in the long term, so I guess I just hope that by bringing people’s attention to this particular moment, and showing them that it is a good time for television, movies, books, and music, that we’ll be able to hold onto it for as long as possible.

My point here is really to bring attention to the New Sincerity movement and to highlight the positive effect it is having on popular culture. I’m under no illusions that any pop culture moment is sustainable in the long term, so I guess I just hope that by bringing people’s attention to this particular moment, and showing them that it is a good time for television, movies, books, and music, that we’ll be able to hold onto it for as long as possible.

5. What implications are there, specifically, for Christian readers?

While the book wasn’t written for an exclusively Christian audience, Christianity is the perspective I’m writing from and it greatly informs the book’s central investigation — the search for good and moral truth in pop culture. For Christians, I think it is important to know that these kinds of things are out there. That, though we need to use discernment, we shouldn’t write off a musician because he or she uses profanities or block ourselves off from some amazing stories because a film may have some elicit sexual content.

I hope that by showing what is good about popular culture, I can convince believers to approach it critically but with a keen eye for the truth that pop culture practitioners are communicating. I worry that Christians — and evangelicals in particular — lock themselves up in a protective bubble under the guise of “purity,” but this does more harm than good. We are completely ineffective and irrelevant when we imagine we’re not a part of the larger culture.

6. What’s next for you?

My roots as a writer are in creative writing — fiction, actually. And while I don’t feel quite ready to leap back into fiction, I’m working on a book proposal now that will allow me to creatively tell a story as a means of getting across a point. I do some of that in Not Your Mother’s Morals, but this next project, I hope, will be a bit more like a memoir than an essay.