Following up on my last post, which likely changed your life forever, let’s channel Gary Rendsburg’s article a bit more and explore a few more ways that David and the monarchy are embedded into the stories in Genesis (in no particular order).

Esau’s “blessing” and Edom’s revolt. You may recall in Genesis that younger brother Jacob twice outmaneuvered his elder brother Esau (nickname Edom, Genesis 25:25 and 30).

The first time (Genesis 25:29-34), Esau (who is clearly some kind of dolt), sold his rights as firstborn for a hot lunch. As far as I’m concerned, that one’s on Esau. But in 27:1-40, Jacob, at the urging of his helicopter mother Rebekah, tricked old, nearly blind, Isaac into giving him Esau’s blessing too (by dressing up as Esau).

After Isaac blesses Jacob by mistake with a very awesome blessing that really couldn’t be topped (27:27-29), Esau returned from his hunt (the brutish, hairy guy is always out hunting) expecting to be blessed by his father. Isaac realizes he has been deceived, basically freaks out, followed by Esau freaking out even more, begging his father, “Have you only one blessing, father? Bless me, me also, father?” (v. 38)

Yes, Esau. Jacob only has one blessing, and he shot it all on Jacob. And it’s quite a blessing, which includes agricultural bounty and—to get to our point—political supremacy:

Let peoples serve you, and nations bow down to you. Be lord over your brothers, and may your mother’s sons bow down to you. (27:29)

Looks to me, Esau, that you’ll be under your brother’s thumb. (You really need to stay home more and keep an eye on things.)

The plural “brothers” and “your mother’s sons” may seem odd at first blush, given that Jacob only has one brother, the disenfranchised Esau. But in Hebrew “brothers” and “sons” often simply mean “kin” and “descendants.” And these plurals are a clue as to the ultimate meaning of this exchange.

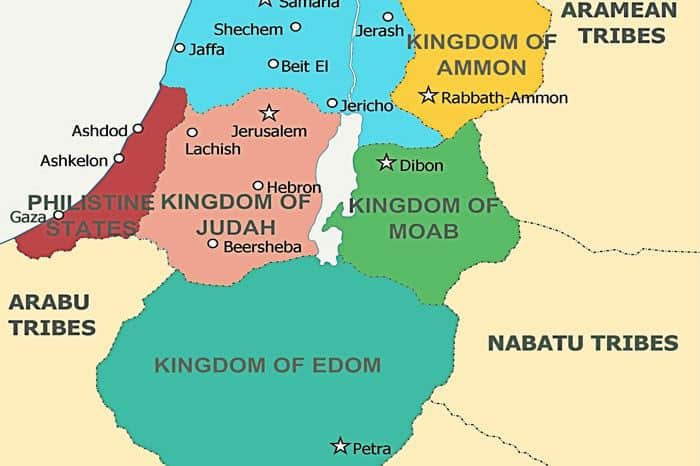

If we remember that Jacob’s name will be changed to Israel later in the story (32:28 and 35:10), it’s not to hard to see what is really being said here: the Israelites will have political supremacy of their kin—which include Edom (Esau’s nickname) and the other two trans-Jordan nations: Ammon and Moab.

Like Edom/Esau, Ammon and Moab are also kin, but more distantly. As Genesis tells the story, these nations stem from the union of Lot (Abraham’s nephew, Isaac’s cousin) and his daughters (19:30-38)—and if that’s not political propaganda, I don’t know what is.

The plurals “brothers” and “sons” make perfect sense if we see in Genesis later political realities embedded into the past. Genesis draws up Israel’s political map, and the younger son of Jacob will reign over them.

Back to Esau. Isaac has exhausted his good blessing by giving it to Jacob, and so he has to scrounge up a blessing for Esau. And this is all he has left (vv. 39-40):

See, away from the fatness of the earth shall your home be, and away from the dew of heaven on high. By your sword you shall live, and you shall serve your brother; but when you break loose, you shall break his yoke from your neck.

Not much of a blessing. Sort of an anti-blessing if you ask me, the opposite of Jacob’s: weak agriculture and political subservience—but with one ray of hope: Esau/Edom will eventually break free from his brother.

And so he does.

According to 2 Samuel 8:13-14, the nation of Edom came under Israelite control under David and then revolted about 150 years later during the reign of the southern (Judahite) king Jehoram (2 Kings 8:20-24).

And so, Esau/Edom served his brother for a time until he broke loose. It seems like Isaac’s “blessing” to Esau was preview of coming attractions pertaining to the political events of the middle of the 9th c. BCE.

As we saw in the last post, the monarchy is the context for the writing of Genesis, and monarchic concerns are embedded into the ancient narratives of Genesis.

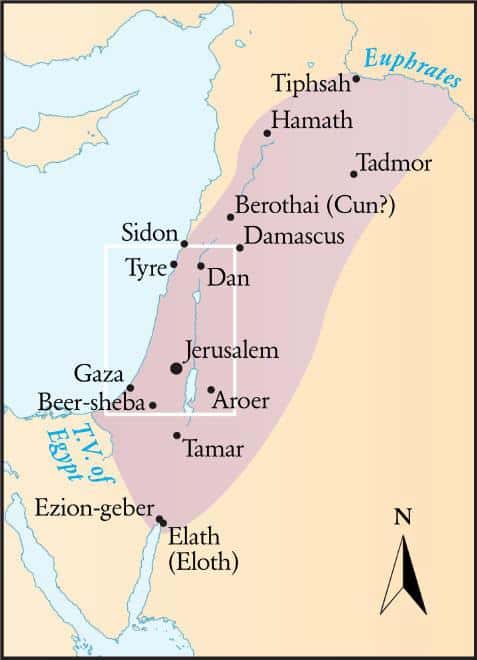

Israel’s ideal boundaries. In Genesis 15:18, God promises Abraham the land of Canaan for his descendants. The description of the boundaries is extensive—stemming from the Euphrates River down to Egypt.

These extensive boundaries appear elsewhere in the Israel’s story only during the time of the monarchy, specifically the early, ideal, days of the monarchy during the reign of Solomon (1 Kings 4:20-21) before he got cocky and disobedient.

The promise to Abraham was written with the monarchy in view—not predictively but retrospectively.

Abraham’s near sacrifice of Isaac. In this famous story (Genesis 22), Abraham’s near sacrifice of his son Isaac is stopped at the last second when God provided a ram for the sacrifice as a substitute. The story ends,

So Abraham called that place, “The LORD will provide”; as it is said to this day, “On the mount of the LORD it shall be provided.” (v. 14)

Here is the earliest reference in the Old Testament to the “mount of the LORD,” and the other occurrences (in Isaiah, Micah, and Psalm 24) all refer to Mount Zion, which is Jerusalem with its Temple built during the reign of Solomon.

The writer of this story is living during the monarchic period (“as it is said to this day”) and embedding the origins of Temple sacrifice in the near sacrifice of Isaac, where an animal was substituted for a human.

The everlasting covenant. The Hebrew term berit `olam (everlasting covenant) is used in the Old Testament of only 3 people: Noah (Genesis 9:16), Abraham (Genesis 17), and David (2 Samuel 23:5). God’s relationship with David is like one we have not seen for a long time, since the dawn of time, since Israel’s beginnings.

There are more examples in the article—some a little subtle, others that take a lot more explaining. But the similarities between the stories in Genesis and the later monarchy that we’ve looked at here and in the last post are hard to dismiss.

Key elements of the monarchy find their origin in the deep past of Israel’s origins. To read Genesis well means to read it with one eye on David, the monarchy, and ultimately the southern nation of Judah.

This way of looking at Genesis may be seem to some to undercut the Bible, and I get that. But it’s not. It’s really only about trying to understand when and why Genesis was written by paying careful attention to the clues the writer left there.