Recently, Al Mohler, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, led a panel discussion called “Revisiting Inerrancy: The Challenges Continue.” He was joined by four of his faculty members: three theologians (Russell Moore, Gregg Allison, Bruce Ware) and one New Testament professor (Denny Burk, from SBTS’s undergraduate feeder school Boyce College).

Recently, Al Mohler, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, led a panel discussion called “Revisiting Inerrancy: The Challenges Continue.” He was joined by four of his faculty members: three theologians (Russell Moore, Gregg Allison, Bruce Ware) and one New Testament professor (Denny Burk, from SBTS’s undergraduate feeder school Boyce College).

Mohler felt it was their responsibility as “good stewards” of Scripture to speak “truthfully” about the Bible and to have that discussion videotaped for general viewing and edification. Their concern was to refute the continued “attacks” on inerrancy from outside and inside of evangelicalism that threaten Christian orthodoxy.

I watched the video in part, because, along with Al Mohler (and Kevin Vanhoozer, Michael Bird, and John Franke), I am contributing an essay for a volume on inerrancy in Zondervan’s popular “Counterpoints” series. Actually (my editors are happy to know) I completed (note deliberate use of past tense) my essay over two weeks ago, but I watched the video nevertheless to see if by some chance I might hear something new–either in content or tone–that suggested some acknowledgement of the value of the broader discussion happening in American Fundagelicalism (which is what prompted the Zondervan volume in the first place).

I was disappointed but not surprised. For an hour, Mohler and his colleagues expounded, with great confidence, on the unimpeachable and foundational role inerrancy plays in Christian theology. Any attempt to “revisit” inerrancy within evangelicalism is nothing more than an “attack” on inerrancy, no different in principle from outside “liberal” attacks.

From my point of view, however, I saw little more than a circling of the wagons: the perpetuation of familiar, unconvincing, and in some cases intellectually isolated, arguments that rest on allegedly unassailable theological assertions of the nature of God, Christ, and Scripture, and the demonizing (almost literally, see below) of those who think otherwise.

I list below 34 points made by the panelists in the course of the hour long discussion (mainly paraphrased). I considered  grouping them under general categories, but I decided to reflect as much as I could the rhythm and flow of the panel discussion. Hence, you will certainly see some repetition in my 34 points, as the panelists tended to repeat themselves on what they likely considered to be their stronger arguments, including some version of (1) “inerrancy goes back to Jesus at least and has run unfettered throughout church history until recently,” and (2) “why in the world do we have to keep defending something that is so clearly self-evident (biblically, logically) it shouldn’t need defending?”

grouping them under general categories, but I decided to reflect as much as I could the rhythm and flow of the panel discussion. Hence, you will certainly see some repetition in my 34 points, as the panelists tended to repeat themselves on what they likely considered to be their stronger arguments, including some version of (1) “inerrancy goes back to Jesus at least and has run unfettered throughout church history until recently,” and (2) “why in the world do we have to keep defending something that is so clearly self-evident (biblically, logically) it shouldn’t need defending?”

Some brief thoughts of my own are in italics.

1. Inerrancy did not really need to be defended until the 1960s. [This sets the stage for insinuating that those who question inerrancy are part of a fad or trend that can be easily discounted. Others on the panel later refer to movements in the 19th century and earlier, but the rhetorical effect of this opening jab is clear.]

2. Let’s make sure we all define inerrancy so we all know what it is and what it isn’t: “The Bible is true in all that it affirms or teaches according to the author’s intended meaning.” [Determining what an author intended and what Scripture “affirms and teaches” are hermeneutical and theological exercises, not simply derived from a “plain” reading of Scripture. Phrasing things this way is also a bit of an escape clause, i.e., the fact that the Bible presents the world as flat and allows for holding slaves does not obligate inerrantist to do likewise, since the biblical author never “intended” this to be a “teaching.” Of course, this raises the question, “How do you know that?”]

3. Good solid inerrantist evangelicals go to Harvard, etc., and before you know it they are caught up in the need to be intellectually respectable, and the first thing to go is inerrancy. [Is it possible that the reason inerrancy is the “first thing to go” is because its arguments are weak in view of information, and students feel somewhat betrayed at having been isolated from it? The insinuation that questioning inerrancy is a problem of sinful pride, though a common caricature, rings hollow to those whose faith crises grew in the fertile soil of Mohler’s brand of fundamentalism.]

4. Inerrancy grows out of who God is, so if you lose inerrancy your entire theology is suspect. This is why now, more than ever, the church has to be protected from attacks against inerrancy. [Linking God with inerrancy as an inescapable premise of Christian logic is in a nutshell the entire problem. Hence, attacking inerrancy is seen as an attack on the Bible, and thus on God himself. Questioning inerrancy, however, is really only an attack on a theological system that requires it.]

4. Inerrancy grows out of who God is, so if you lose inerrancy your entire theology is suspect. This is why now, more than ever, the church has to be protected from attacks against inerrancy. [Linking God with inerrancy as an inescapable premise of Christian logic is in a nutshell the entire problem. Hence, attacking inerrancy is seen as an attack on the Bible, and thus on God himself. Questioning inerrancy, however, is really only an attack on a theological system that requires it.]

5. And now, even evangelicals are attacking inerrancy from the inside. It all started with Jack Rogers and Donald McKim, and Kent Sparks and Brian McLaren are continuing the downward spiral. [The work of Rogers and McKim, which questioned the evangelical premise that inerrancy has always been the church’s view of the Bible, was countered by John Woodbridge

(see below). Leaving aside the specifics of the arguments, it is part of evangelical lore that Woodbridge has finally and definitively defended the evangelical position. Raising the work of Sparks and McLaren in conjunction with Rogers/McKim is a rhetorical move to paint them all with the same brush. This is a common fundamentalist debating technique, to line up previous enemies with current ones and say the new arguments are simply rehashed old ones (see below), and therefore the victories of the warriors of the past can be effortlessly transposed to the present.]

6. Infallibility (rather than inerrancy) is not good enough, since it allows for historical and scientific errors in the Bible. [Commonly recognized historical and scientific pressure points for revisiting inerrancy leads many evangelicals to prefer the softer language of infallibility. The panelists feel that infallibility opens to door to allowing that evidence into the conversation, and so is kept outside the gate. Simply put, whatever threatens inerrancy is neutralized at the outset.]

7. We [amazingly] keep having to defend inerrancy and have these same discussions “decade after decade.” [Yes you do–and there may be good reasons why. Perhaps the arguments are not persuasive.]

8 The Bible itself teaches inerrancy (a.k.a. Jesus was an inerrantist). [Here familiar prooftexts are raised, as if needing no further defense, that allegedly demonstrate that the Bible never errs, such as 2 Timothy 3:16; John 17:17.]

9. Since God is truth, an inerrant Bible is his only option. [See #4]

10. Inerrancy has always been the position of the church. [A high view of Scripture has certainly been the church’s position, but the modern articulation of inerrancy and the role that articulation plays in fundamentalism, most certainly were not. I am entirely confident that if a faculty candidiate at SBTS would say some of what Luther and Calvin said about the Bible, they would be unhireable.]

11. Inerrancy requires plenary verbal inspiration, not merely “conceptual” inspiration. [This is a jab at Fuller Seminary’s turn to dark side when it reformulated its doctrine of Scripture away from the view that Mohler et al. feel is crucial to maintain. There is apparently nothing of value to be gained in considering the rasons why Fuller did what it did. They were simply wrong and Mohler et al. are right.]

12. Without inerrancy, our “theological superstructure” collapses, especially our doctrine of God. [Yes, I agree. The kind of theological superstructure and God Mohler requires collapses without an inerrant Bible. So, maybe it is also time to revisit Mohler’s theology.]

13. Non-inerrantists make themselves a papal-like authority over Scripture; they get to determine what is and is not authoritative (the “all or nothing” argument). [Every Bible reader, including Mohler, makes decisions on every page about what is and is not authoritative–i.e., what Scripture “teaches or affirms” (see #2).]

14. Challenges to inerrancy are modern. [See above.]

15. A new generation of evangelicals needs to be protected from attacks on inerrancy. [The new generation of evangelicals I know want to be protected from untenable arguments posed as theological non-negotiables.]

16. We keep having the “same discussions in different clothes.” [Again, the “this is nothing new” argument.]

17. Denying inerrancy leads to Mormonism. [Scare tactic, guilt by association, cheap shot.]

18. John Woodbridge definitively and permanently showed, against Rogers and McKim, that inerrancy was not invented in the 19th century but has always been what the church believed. [See #5. Despite claims to the contrary, B. B. Warfield, John Calvin, Martin Luther, Thomas Aquinas, Augustine–along with Paul and Jesus–hold views of Scripture and used Scripture in ways that don’t line up with what inerrantists require of the Bible.]

not invented in the 19th century but has always been what the church believed. [See #5. Despite claims to the contrary, B. B. Warfield, John Calvin, Martin Luther, Thomas Aquinas, Augustine–along with Paul and Jesus–hold views of Scripture and used Scripture in ways that don’t line up with what inerrantists require of the Bible.]

19. The denial of #18 is intellectual dishonesty. [Within an inerrantist system, yes.]

20. Opponents of inerrancy are guilty of a “crafty use of language” (like saying the Bible can be “true” without being inerrant). [Inerrantists are guilty of thinking that “truth” has a static meaning, and that what they mean by truth is what God means. The use of “crafty” to describe their opponents echoes the serpent’s temptation of Eve in the Garden of Eden (Genesis 3:1). This is not likely to encourage conversation, since the serpent is understood to be Satan. The connection between non-inerrantists and the serpent is more explicit below.]

21. They are amazed about “Young wags, theologians…who think the history of theology began with them” rather than realizing their objections to inerrancy are “all old news.” [Here questioning inerrancy is due to youthful ignorance and arrogance in addition to pride (# 3 above).]

22. Evangelical objections to inerrancy simply repeat the arguments that previous generations of Evangelicals effectively dismantled. All those objections have been fully answered. [A slight variation on the dominant theme of the panel discussion: “You’re wrong because you disagree with our past.”]

23. Evangelicals just need to pay closer attention to the nuanced and sophisticated work of those who produced the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, which is a “statement of incredible genius.” [Mohler et al. may not be aware of the the history of criticism of CSBI. Not all share his view, and the authors of the above-mentioned Zondervan volume have been asked to offer an evaluation of CSBI.]

24. Inerrancy is not a simplistic way of looking at the Bible. It can account for things like the use of “round numbers” and “phenomenological” observations like “the sun rises.” [Yes, of course, we all know that the use of round numbers in the Bible is not an error. Neither is speaking of the sun rising since we do the same thing. What this argument constantly overlooks, however, is that round numbers and phenomenological language are not the same thing. Biblical figures actually believed the sun rose and the earth was flat–they “affirmed” these things. These (and other) examples represent ancient ways of thinking (not just speaking) about their world, but Mohler et al. are loath to allow the biblical authors to be fully constituted members of their time and place in the human drama. When an ancient biblical writer says “the sun rose,” he does not mean what we mean. Inerrantists really need to move on from this argument.]

25. The attack on inerrancy began in the serpent in the Garden of Eden who put doubt in Eve’s mind about what God said. Inerrancy, therefore, is a matter of spiritual warfare agains the “powers and principalities of the sky.” [This type of argument, regrettably common, is considered the knockout blow. It think it is unworthy of reasoned Christlike discourse. See #20 above.]

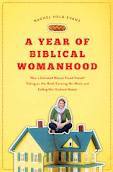

26. Rachel Held Evans in her recent book (A Year of Biblical Womanhood: a Liberated Woman Found Herself Sitting on Her Roof, Covering Her Head, and Calling Her Husband “Master”

26. Rachel Held Evans in her recent book (A Year of Biblical Womanhood: a Liberated Woman Found Herself Sitting on Her Roof, Covering Her Head, and Calling Her Husband “Master”) is “mocking the Bible” and showing it “overt derision.” [Evans is not mocking the Bible but biblical literalism. That is the entire point of the book, and I am surprised the panelists missed it. Their offense at Evans’s book is rooted in the false assumption that literalism is the default proper approach to Scripture, and so to attack literalism is to attack the Bible, Christianity, and God himself.]

27. My use of an incarnational model of Scripture in Inspiration and Incarnation: Evangelicals and the Problem of the Old Testament is a “frontal assault” on inerrancy. [See #26. I am disappointed they have come to this conclusion, particularly since an incarnational model is far, far, older than inerrancy or my use of it. I am, however, somewhat relieved that the panelists finally got around to mentioning me. I was beginning to wonder whether they understood that my paradigm and theirs are incompatible.]

28. I am also “overturning all of biblical theology” because of my take on the NT’s use of the OT. [See #s 26  and 27. In a nutshell, as I explain in Inspiration and Incarnation and more recently in The Evolution of Adam: What the Bible Does and Doesn’t Say about Human Origins

and 27. In a nutshell, as I explain in Inspiration and Incarnation and more recently in The Evolution of Adam: What the Bible Does and Doesn’t Say about Human Origins, when the New Testament authors interpret the Old Testament, they are certainly not doing it in an inerrantist way–which is understandably a major problem for inerrantist, and so I can appreciate their overblown rhetoric here. They are welcome to make their case for an alternative view, however.]

30. The “ever since the Enlightenment” argument. [The ultimate conversation stopper is to claim that inerrancy’s opponents, rather than obeying God, are beholden to Enlightenment philosophy, which rejected divine authority. I am genuinely surprised it took them this long to play this card.]

31. Without an inerrant Bible, we have no external authority and so we become the authority. [No external authority? God? The Spirit? Jesus? See above at various places.]

32. Kent Sparks’s views put him on the road to Christopher Hitches (and the crafty serpent in the Garden of Eden). [Maybe yes, maybe no, but you do not know that, and so maybe turning down the rhetoric is a good idea. Also, does not your road lead anywhere, like legalism and Phariseeism? Is there a log in your eye?]

33. Evangelical deniers of inerrancy think they need to be intellectually accountable to the “New Atheists.” [Or perhaps they find their arguments worthy of reasoned engagement. Here the “pride” card is played again. See #3.]

34. Affirming inerrancy is a show of Christian humility. [So is being willing to listen–really listen–to those who say you are wrong, especially if you share a common faith with them.]

It is of no concern of mine whatsoever what Mohler thinks about how the Bible has to be. Mohler and his faculty are absolutely free to believe as they wish, and my purpose in this life is not to change their minds, ridicule them, crush them, mock them, or whatever. My concern is to help those who feel trapped by Mohler’s way of thinking, people with whom I have had many conversations over the years.

They need to hear that the boundaries drawn in panel discussions like this do not reflect all or the best of the Christian tradition. Rather they sell God and the Bible woefully short by placing burdens on the text–and its readers–that neither should, or can, bear.