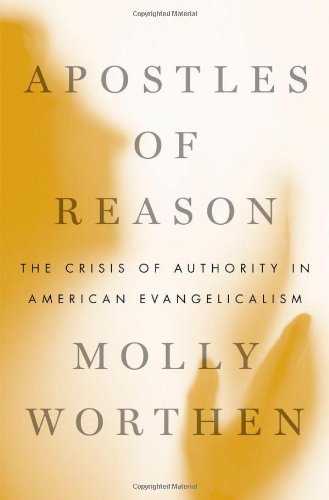

I received in the mail yesterday a copy of Molly Worthen’s Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism. Despite a very heavy football and couch-potato schedule this weekend, I am am nevertheless more than half done with it and I want to throw out a few quotes now and then–beginning today.

I received in the mail yesterday a copy of Molly Worthen’s Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism. Despite a very heavy football and couch-potato schedule this weekend, I am am nevertheless more than half done with it and I want to throw out a few quotes now and then–beginning today.

In her closing comments of the introduction, Worthen talks about “The Problem of Anti-Intellectualism” in evangelicalism (pp. 8-11). For her the matter is more complicated that a sweeping and simplistic accusation. Evangelical anti-intellectualism is part of the “larger narrative of Western intellectual history” (p. 7), which contains an uneasy marriage between Pietism (religion is a matter of the heart) and the Enlightenment (rebirth of reason and its many challenges to traditional thinking). She calls these two ideals evangelicalism’s “estranged parents” (p. 7; which implies, among other things, that evangelicalism’s existence is tied to the Enlightenment, even as it tries to keep its distance from it, a point some future quotes will draw out further).

So, concerning Evangelical anti-intellectualism, Worthen remarks,

The evolution of the evangelical community–and whether, and why, it might be called anti-intellectual–is best traced through the lives of the elites: the preachers, teachers, writers, and institution-builders in the business of creating and disseminating ideas. When critics describe evangelicalism as anti-intellectual, usually they are not blaming ordinary laypeople. A casual glance at the latest Amazon.com best-seller list, chock full of celebrity memoirs and pulpy novels, or the amateur talent shows and dating competitions that top the television rating, demonstrates that when it comes to intellectual shallowness evangelicals have no advantage on the rest of America. When critics condemn the “evangelical mind,” they are talking about the people who ought to know better, who bear some responsibility for the Darwin-bashing and history-hashing that pollsters hear when they survey evangelical America. They are comparing evangelical elites with the nonevangelical intelligentsia. They are asking how it can be that college professors believe in creationism, or that educated activists deny evidence of global warming. They are wondering how evangelicals define the purpose of higher education (for which they have long shown great zeal) when they so regularly demean the fruits of critical inquiry, and how they can reconcile their fervor for evangelism with American pluralism. (pp. 9-10)

teachers, writers, and institution-builders in the business of creating and disseminating ideas. When critics describe evangelicalism as anti-intellectual, usually they are not blaming ordinary laypeople. A casual glance at the latest Amazon.com best-seller list, chock full of celebrity memoirs and pulpy novels, or the amateur talent shows and dating competitions that top the television rating, demonstrates that when it comes to intellectual shallowness evangelicals have no advantage on the rest of America. When critics condemn the “evangelical mind,” they are talking about the people who ought to know better, who bear some responsibility for the Darwin-bashing and history-hashing that pollsters hear when they survey evangelical America. They are comparing evangelical elites with the nonevangelical intelligentsia. They are asking how it can be that college professors believe in creationism, or that educated activists deny evidence of global warming. They are wondering how evangelicals define the purpose of higher education (for which they have long shown great zeal) when they so regularly demean the fruits of critical inquiry, and how they can reconcile their fervor for evangelism with American pluralism. (pp. 9-10)

Do you experiences confirm or deny Worthen’s observations?