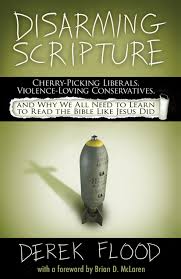

Today’s post is an interview with Derek Flood, author of Disarming Scripture: Cherry-Picking Liberals, Violence-Loving Conservatives, and Why We All Need to Learn to Read the Bible Like Jesus Did, which has just been released this week.

Today’s post is an interview with Derek Flood, author of Disarming Scripture: Cherry-Picking Liberals, Violence-Loving Conservatives, and Why We All Need to Learn to Read the Bible Like Jesus Did, which has just been released this week.

The book deals with the problem of violence in Scripture, tackling a wide range of troubling passages—from commands to commit genocide and infanticide in the Old Testament to passages in the New Testament that have been used to justify slavery, child abuse, and state violence. Flood is also author of Healing the Gospel: A Radical Vision for Grace, Justice, and the Cross. His blog is The Rebel God and he also blogs at Red Letter Christians, Sojourners, and the Huffington Post.

Flood argues that learning to read Scripture like Jesus did will move us beyond typical conservative and liberal approaches, which seek to either defend or whitewash violence in the Bible.

Many Christians struggle with the Bible’s violent passages and commands, especially in the Old Testament. They ask, “How can I believe in a God who orders people to commit genocide or women to be taken in as sex slaves?” Where do you start to address these objections?

There’s often an assumption that these are the objections of atheists, and so the Christian response needs to be to defend the Bible. My own experience, however, was that the more time I spent with Jesus, the more I got to really understand his heart for the lost, the more troubled I became at the violence in Scripture—particularly human violence in God’s name. In other words, the problem I had with violence in the Bible was not a result of a weak faith, but the result of growing deeper in my faith. It was the result of a mature faith.

Still, I felt a conflict because I was questioning my own sacred Scripture. What I discovered as I began to dig into this though was that exactly that kind of questioning was all over the Bible. We find it in the psalmist’s complaints, in the prophets, in Job, in Ecclesiastes, and following in that same line of faithful questioning so characteristic of the Hebrew Bible, we also find that questioning in the name of compassion continued in Jesus and Paul.

So what I would want to say to those who are struggling, wrestling, questioning with violence in the Bible is that you are in some very good company, and that the biblical canon itself invites us, calls us to question. So what I try to demonstrate in my book, looking at the examples of both Paul and Jesus is that we don’t need to stop questioning. Rather, we need to learn to do it well so it leads us to love better and grow closer to Jesus. That’s what faithfulness looks like

Some would object here that since we as humans have a fallen nature, our sense of morality is broken. So how can we question the Bible? Shouldn’t we let the Bible decide what is right or wrong?

The choice is not so much between our fallen morality and the Bible, but between our fallen and limited morality and our fallen and limited interpretation of the Bible. In other words, everything we do goes through our broken lens—including our interpretation of Scripture. So rather than shutting down our brains and conscience as we read, we need to instead learn to read with our hearts and minds fully engaged.

That of course is not a guarantee that we will get everything right. We won’t. That’s a reality that we need to face as adults. But the reality is that when we read the text blindly in a “the Bible said it, that settles it” unquestioning kind of way, we are virtually guaranteed to get it wrong. As evidence for this we just need to look at the long history of how people have used Scripture to justify all sorts of atrocities and hurt.

Questioning is good. Questioning is an act of faith. To not question is dangerous because it means shutting down our conscience, and history shows over and over that really terrible things happen when people do that.

Also I’d want to point out the fact that the Bible—and in particular the Old Testament—is simply not one single view. It contains a multitude of conflicting views, from different authors in different times with different beliefs. For example, some parts of the Old Testament teach that foreigners are corrupting and should be expelled or killed, other parts say in contrast that they should be sheltered and treated with compassion.

That’s just one example of a pattern that we find over and over again in the OT. We don’t find a single view, but a record of dispute with differing understandings of what faithfulness looks like, side by side within the Hebrew canon. That reality means that we must choose between these conflicting views. To do that we need to think, to question, to wrestle.

That kind of questioning is typical of Jewish biblical interpretation—after all, the very name “Israel” literally means “wrestles with God.” It is also something we see Jesus doing constantly (which is not surprising since he was Jewish). Yet for some reason we Christians have been taught to think that questioning is bad, that it is a threat to the faith rather than a way to strengthen it. In fact, there is a history of branding those who question as “heretics” and seeking to use violence to silence them.

That’s tragic because it means we lose the art of encountering the text morally when we forbid questioning and conscience. If we want to read Scripture as Scripture we must learn to engage it morally.

What do you make of the places where Jesus seems to affirm God’s violent judgment in the New Testament? For example, Jesus “predicts” the violent end of Jerusalem and seems to be fine with it. How would you respond to that?

Well, first, I’d want to clarify that when you say Jesus did not have a problem with it, what this means is that he did not see a conflict in calling us to a life of radical forgiveness and enemy-love while at the same time affirming God’s judgment for those who instead follow in the way of violence. That of course does not mean that Jesus was okay with people’s suffering. It says, Jesus “wept” over Jerusalem.

In seeking to understand this, it’s critical not to miss the big picture. That is, many of us today struggle so much with this understanding of God’s judgment that we can miss the radical shift that is taking place in regards to the NT’s message of how we humans are to live—the huge move of the NT away from the idea that justice comes through human acts of violence.

That was the common assumption at the time—they believed God’s kingdom came through people killing in God’s name. This was why the people expected the messiah to come as a violent warrior-king. We find human violence in God’s name affirmed throughout the Old Testament, too—for example in the divine commands for people to commit genocide.

So there is an absolutely huge shift taking place in rejecting the idea of humans killing others in God’s name. The NT rejects that way and calls followers of Jesus to a life of forgiveness and enemy-love. So what we have here is agreement within the NT in proclaiming that our way as followers of Jesus is a way of radical forgiveness and enemy-love, as opposed to the way of violence in God’s name.

There is, however, within the NT diversity in how we are to live out that way of Jesus. In some NT writers (for example Matthew’s depiction of Jesus as opposed to the other Gospels) we see a belief in God’s judgment as integral to our following in the way of Jesus—similar perhaps to Miroslav Volf who insists “the practice of nonviolence requires the belief in God’s vengeance.” Elsewhere in the NT we find a different view of God expressed, but again the same focus in our need to act in compassion and enemy love.

What this means is that rather than one way, we find a conversation in the NT about how to live out the way of Jesus. This invites us to enter into that conversation, too. That means that we need to work out what it means to love our enemies today, what it means to care for the poor, how we can resolve conflicts, work for justice, and so on.

The bottom line here is that Jesus demonstrates a way of questioning the cultural and religious assumptions of his time in order to pull people towards greater love. To read Scripture in our time like Jesus did requires that we learn to ask those same kinds of questions—questioning ourselves, our culture, and our religious assumptions, including our assumptions of how we read the Bible.

The goal in all of this is to read Scripture in a way that leads to greater love. We don’t get there by shutting down our brains and conscience, but by fully engaging them as we read.