A few days ago I posted on my recent trip to the annual biblical scholars’ academic meeting, the Society of Biblical Literature, held this year in Baltimore’s “Inner Harbor.” (If you prefer outer harbors, you’ll have to go to Buffalo or Australia.)

A few days ago I posted on my recent trip to the annual biblical scholars’ academic meeting, the Society of Biblical Literature, held this year in Baltimore’s “Inner Harbor.” (If you prefer outer harbors, you’ll have to go to Buffalo or Australia.)

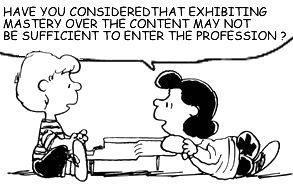

One thing I didn’t mention there is something that weighs heavily on me (see here with links to other posts), and I am reminded of it each year at SBL: talented and promising scholars–who have much to offer, could potentially wind up being significant voices in the field, and have PhDs in hand–can’t get jobs.

Which makes me wonder, yet again, about the ethics of institutions accepting students to train them for jobs that don’t exist.

Schools have all sorts of reasons–overlapping and complex–for offering degrees in Biblical Studies (which normally includes related areas like ancient Near Eastern studies, early Judaism, early Christianity, and things like that).

- The institution has a long tradition of granting such degrees.

- Discontinuing PhD programs in Biblical Studies would put a lot of people out of work, and that’s an especially tricky business when endowed chairs are in the mix.

- Biblical Studies is a valued field for that school’s mission and purpose.

- Granting PhDs lends prestige to the school.

- PhDs trained in a school’s ideology can further that school’s ideology.

- PhD programs are potential sources of revenue.

These reasons are, in the abstract, neither right nor wrong. They just are what they are. But regardless, if jobs do not exist for a vast majority of those trained to fill them, something is broken and it needs to be fixed.

What further complicates the matter, and reduces job openings even more, is the move toward the use of adjuncts rather than hiring full time, tenure track professors.

I had several conversations this year at SBL with freshly minted, soon-to-be minted, and have-been-minted-for-quite-some-time-now-thank-you-very-much PhDs all highly competent and all elbowing for the same few, precious, underpaying jobs with heavy workloads. One recent opening received over 200 applicants. Schools with confessional commitments are more self-selecting in their applicant pools–one I know of got over 100.

Perhaps PhD programs should look at their track records over, say, the last ten years to see how many of their graduates found work either as they were completing their degrees or within 2 years of completing them. And by “work” I mean full time, gainful employment in the field of their choice–you know, a job–and not “settling” for teaching Bible at a private Christian high school, pastoring, or any other plan B.

If the average is, say, 2 per year, rather than admit the number of students needed to sustain the program (which I know from experience happens), admit 2 to 4 students and see how that goes for a few years. And be absolutely clear with the applicants, letting them know what the school’s track record is for graduates finding conventional work in the field. (Students who enter with non-conventional career aspirations–e.g., missionary work, pastoring, secondary school education–are not affected by these same market realities and comprise another category of applicant entirely.)

But the bottom line is let the applicants know what they are getting themselves into, what career paths are likely open to them. Applicants should do their homework before entering a PhD program, but they don’t. And often their college or seminary professors don’t think to sit their students down and give them the 4-1-1.

I am glad I no longer teach doctoral students for careers in Biblical Studies. I would feel dirty.

I’m not sure, practically speaking, what can be done about it. Perhaps if students simply stopped applying for doctoral programs for a few years, the institutional problem would take care of itself.