Here’s an observation I’ve been pondering for a few years but never thought to put it in writing until now. No big reason why. I just never got to it.

Here’s an observation I’ve been pondering for a few years but never thought to put it in writing until now. No big reason why. I just never got to it.

I’ve observed a revealing parallel between Intelligent Design and conservative/evangelical views of the Bible.

In a word, both tend to get nervous about what I will call, simply as a placeholder name, “natural processes,” where God doesn’t show up in a special, supernatural way.

So, humor me and let me unpack that a bit.

Some sort of evolutionary theory is tolerable for some advocates of ID, but only if punctuated by moments where God does something to intrude into an otherwise “natural” process.

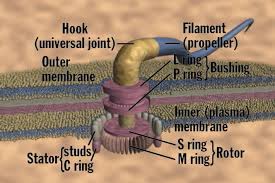

ID research is dedicated to finding and exploiting alleged “gaps” where a naturalistic evolutionary processes would collapse in on itself were it not for God’s direct intervention. A classic example of defending this “God of the gaps” approach is the allegedly “irreducibly complex” motor of the bacterial flagellum.

Conservative views of the Bible work in a similar way. Some level of biblical scholarship is tolerable, as long as, say, the origin and rise of the Bible (to pick one topic) are at the end of the day explained as an act of God’s direct, supernatural intervention–by God coming from the outside, as it were, and invading the “natural” process of men of old thinking, meditating, and writing.

For example, the two histories of Israel’s monarchy–one in the so-called Deuteronomistic History (Samuel and Kings) and the other in 1 and 2 Chronicles–are clearly contradictory (or at the very last in serious tension) on many points. A “natural” explanation is that these histories differ because they were written at different times by different authors for different purposes.

A “God of the gaps” approach to addressing this phenomenon can agree with this “natural” analysis, but only to a point. The “naturalistic” process must in some meaningful sense be punctuated by God’s direct intervention, i.e., inspiring the authors. Evidence of such an intervention must be sought, explicated, and defended in order to show how Scripture necessarily transcends a naturalistic process.

The common way of demonstrating this divine intervention is by arguing for the “basic” or “essential” historical value of these histories, despite their divergencies, and in doing so safeguarding the fundamental divine nature of Scripture.

The common response to ID by theistic evolutionists is that God is actually part of what is erroneously called a “naturalistic” process. Evolution, it is argued (and I agree), is God’s way of creating. Of course, there can be all sorts of philosophical baggage attached to evolution–e.g., that a naturalistic process disproves God, etc. But such philosophical conclusions are rooted, I would argue, in the same mistaken notion that “God’s involvement” is necessarily of an interventionist kind.

Likewise, the, let’s call it, post-evangelical response to a “God of the gaps” process of Bible production will see the Bible’s “evolution” (as it were)–from oral traditions, court records, various legal traditions, etc., to a corpus of material that achieved authoritative status first in postexilic Judaism and then in Christianity–as “God’s way of producing” the Bible.

In both areas–the evolution of life and the “evolution” of the Bible–the issue among Christians is, “What does it mean for God to be involved?” Must it be (1) in some sense that can be discerned and defended as an “outside” intervention”–or–(2) are the processes themselves the way in which God is present?

The problem as I see it is that the kind of evidence needed for #1 doesn’t exist.

In biological evolution, the alleged “gaps” that can only be filled by positing an intervening act of God continue to shrink and do not accord with the evidence, at least as it comes to use from mainstream sources (which includes Christians).

In biblical studies, the necessary interventionist presence of God, seen in the preservation of the “essential” historical accuracy and “essential” univocal theology of its components, is likewise out of accord with the evidence at hand and how that evidence has been interpreted in mainstream scholarship. Biblical scholars disagree, of course, on many things (they always have), but not on the notion that the Bible as we know it is the end product of a complex process of development that can be quite adequately explained without recourse to special outside intervention by God.

One reason why I continue to think that an incarnational model of the nature of Scripture is helpful, rather than other models (like an inerrantist

one), is that it provides some theological language for addressing the phenomenon of Scripture.

And with that, I bid you all a Happy New Year.