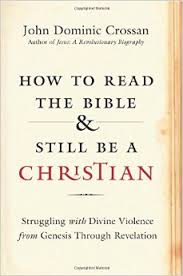

A few weeks ago I read John Dominic Crossan’s new book How to Read the Bible and Still Be a Christian: Struggling with Divine Violence from Genesis Through Revelation

A few weeks ago I read John Dominic Crossan’s new book How to Read the Bible and Still Be a Christian: Struggling with Divine Violence from Genesis Through Revelation, and I would have posted something sooner if I weren’t in the middle of end-of-semester crunch time.

Anyway, enough excuses. The book is thoughtful, energetic, and–that overused but appropriate word–provocative.

Crossan begins by observing, “The biblical God is, on the one hand, a God of nonviolent distributive justice and, on the other hand, a God of violent retributive justice.” (p. 18)

By “biblical God” he means both Testaments of the Christian Bible. By “distributive justice” he means nonviolent justice, God as just, righteous, fair, particularly to the poor, needy, orphaned, oppressed, etc., whereas retributive justice is violent (you know the drill: Flood, Canaanite extermination, taking captive foreign women).

So the operative distinction in the Bible is not so much between a bipolar violent and nonviolent God, but between these two types of justice. And the remainder of the book is more or less an argument that distributive justice is primary whereas retributive justice is secondary.

To put that another way, the Bible gives evidence of a struggle between these two types of justice. Distributive justice reflects the “radicality of God” and retributive justice–here is the big punchline of the book in my opinion–reflects “the standard coercive ways that cultures in fact operate . . . which I call the normalcy of civilization.” (p. 24)

To put that yet another way, distributive justice is God’s “yes,” his “affirmation,” his “assertion” for the world. Retributive justice is the “no,” “negation,” or “subversion” of the primary distributive voice as it is co-opted by the retributive normalcy of human civilizations.

As Crossan summarizes on p. 28,

. . . the heartbeat of the Christian Bible is a recurrent cardiac cycle in which the asserted radicality of God’s nonviolent distributive justice is subverted by the normalcy of civilizations violent retributive justice. And, of course, the most profound annulment is that both assertion and subversion are attributed to the same God or the same Christ (emphasis original).

This is how Crossan explains the diverse portraits of God and Christ in the Bible when it comes to violence: the subversion of the distributively just God of the Bible by retributively violent God of human civilization.

That thesis may not get Crossan many invitations to speak at inerrantist schools or Answers in Genesis, but it makes for a very good read because it makes you think.

I think the following quote from p. 31 summarizes things nicely (emphasis original):

“If the Bible were all good-cop enthusiasm from God, we would have to treat it like textual unreality or utopian fantasy. If it were all about bad-cop vengeance from God, we would not need to justify, say, our last century. But it contains both the assertion of God’s, radical dream for our world and our world’s very successful attempt to replace the divine dream with a human nightmare.

The biblical problem is not, I emphasize, that the recipients of those divine challenges were evil, but that they were normal. The struggle is not between divine good and human evil but between, on the one hand God’s radical dream for an Earth distributed fairly and nonviolently among all its peoples and, on the other hand, civilization’s normal dream for me keeping mine, getting yours, and having more and more, forever. The tension is not between the Good Book and the bad world that is outside the book. It is between the Good Book and the bad world that are both within the book.”

For roughly half the book, Crossan supports his thesis by looking at large chunks of the Old Testament (creation, Deuteronomistic theology, prophecy, wisdom, psalms) before moving on to Jesus and Paul.

Those familiar with Crossan will likely not be surprised at the following (p. 35, emphasis original):

If, for Christians, the biblical Christ is the criterion of the biblical God, then, for Christians, the historical Jesus is the criterion of the biblical Christ.

In other words, the historical Jesus–the Jesus of academic research (whatever problems there might be in locating him), the Jesus before he was “normalized” by civilization and made to be purveyor of retributive justice (think the book of Revelation or the ending to parables like Matthew 13:36-43)–is the true Jesus that trumps the violent Jesus.

Likewise, Paul’s 7 authentic letters represent the radical Paul, the three disputed letters (2 Thessalonians, Colossians, Ephesians) reflect the beginning of a de-radicalizing process,while the 3 pseudo-Pauline letters (1 and 2 Timothy and Titus) are in fully de-radicalized “reactionary” mode to Paul’s radical message.

One example Crossan uses is slavery: The message of Philemon is radically anti-slavery whereas Ephesians 6:5-9 speaks of obeying masters while Titus 2:9-10 speaks of full submission. Crossan sees similar movements concerning the role of women.

Personally, I wasn’t sure how well this idea works for Paul. But Crossan summary point is still intriguing: the radical Jesus and Paul are the climax of the Christian Bible, it’s “nonviolent center [that] judges the (non)sense of its violent ending.” (p. 35)

Like I said, I can predict that not a few people are going to be sorely displeased with Crossan. He will no doubt be accused of “picking and choosing” and “arbitrarily” finding the nonviolent God he wants to see. But he nevertheless adds an angle for addressing a perennial problem in the Bible–and that problem is not simply one of a violent God but of a God whose diverse, even contradictory, descriptions continue to elude convenient and conventional explanations.