Biblical Scholarship for Everyday People.

We help curious people make sense of what the Bible is and what to do with it.

We help curious people make sense of what the Bible is and what to do with it.

WHY B4NP?

The Bible Without

the Baggage

Here, you’ll find thoughtful conversations, trusted scholars, and accessible resources that invite you into deeper understanding. Not certainty for certainty’s sake, but wisdom that makes room for complexity, humility, and growth.

-

Podcast

-

Books

-

Classes

-

Community

The Only God-Ordained Podcast on The Internet

Our podcast is at the core of what we do. We have weekly conversations with experts and scholars like Richard Rohr and Emilie Townes, always coming back to our two big questions: What is the Bible, and what do we do with it?

“My favorite podcast ever, period. It has been a lifeline for me in these tumultuous times, and has deepened and transformed my faith, but certainly not by making it easier.”

— Lovely Listener

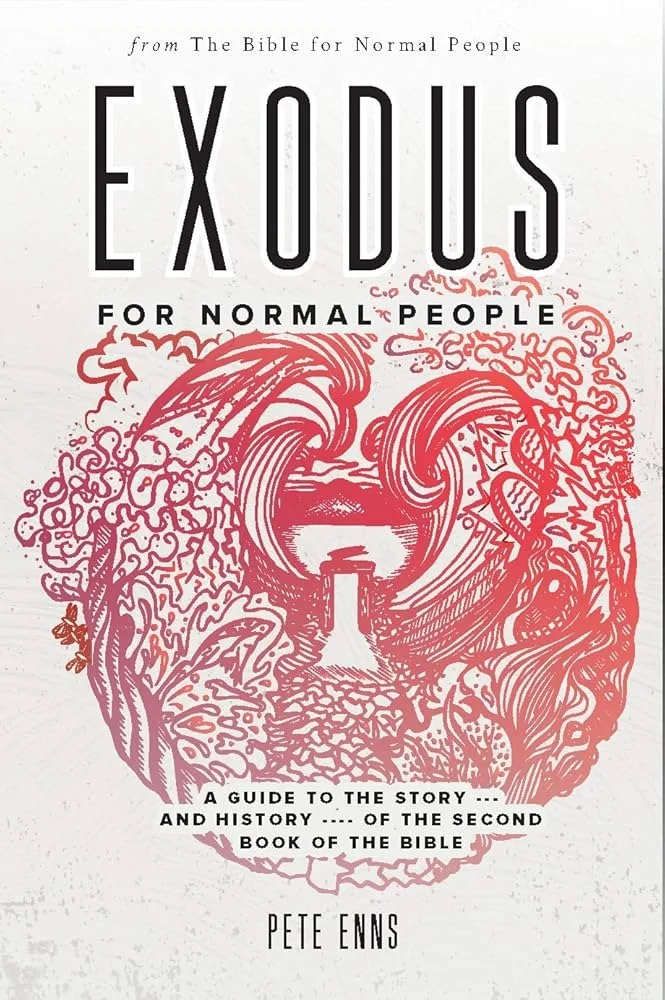

Books for Kinda Normal People

All our books are written for everyday people who want to get smarter about the Bible and stuff. You absolutely need to buy them. Frankly, between us, we’re surprised you haven’t yet.

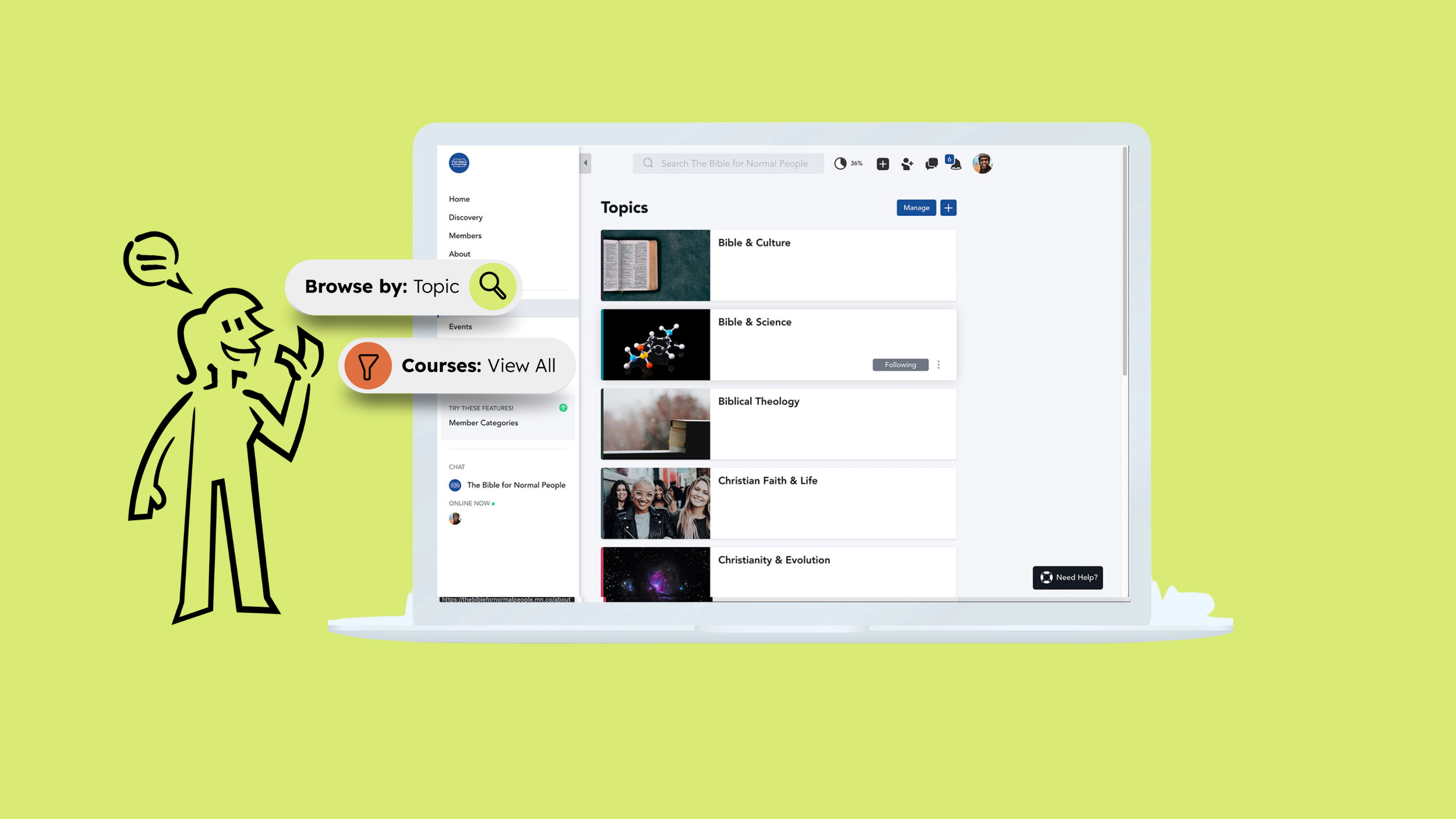

A COMMUNITY MADE FOR YOU

Ready to Learn?

Join Our Platform to Get ALL Our Classes

(Classmates Included!)

Join our Online Platform, the Society of Normal People, and use our app on your phone or computer to get all our classes, forever, for one monthly price. And get a few thousand classmates in a similar place, asking similar questions, for free!

-

You will have complete access to over 50 classes in our library, plus ALL new classes spanning topics like the origins of the Bible, whether hell exists, atonement theories, and so much more!

-

Society members get exclusive bonus episodes of the podcast and an ad-free RSS feed so you can enjoy your episodes uninterrupted.

-

It can be lonely losing a church community when you change your mind about faith or [looks over our shoulder and whispers in a hushed tone] ask questions about the Bible. The Society of Normal People has conversations going all the time, so you can join in!

Introverts: or don’t, we won’t make you. -

Becoming a member of the Society helps sustain the work we do here at B4NP and enables us to continue bringing the best in biblical scholarship to everyday people. And if that sounds like a worthwhile endeavor to you but you don’t need all the perks of membership, our Give page has simpler ways to support us.