There’s been quite a lot of kerfuffle online this summer in the wild and wacky, never boring, but yet always so, world of reading the Bible far, far, too literally.

There’s been quite a lot of kerfuffle online this summer in the wild and wacky, never boring, but yet always so, world of reading the Bible far, far, too literally.

I should put in my two cents—be ready for a shock—that I don’t think much of the recent construction of a life-size but totally non-functional replication of Noah’s ark by Ken Ham and his massive following at Answers in Genesis.

For one thing, I’m not sure what is accomplished, other than, “See, we did it!”—though I assume that, being a business, AiG will realize much gain through it, financial or otherwise. All press is good press, as they say—even if it’s for building an ark (for heaven’s sake).

As is well known, Ham and his organization tirelessly insist that, since the Bible is God’s word, it must be taken literally. This is simply bizarre logic that quickly dissolves once you study the Bible rather than exploit it.

So with that in mind, here are 3 things to keep in front of us if we want to understand the Noah story.

1.The story of the flood seems to be rooted in history. Many biblical scholars relying on geological findings believe that a great deluge in southeastern Mesopotamia along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (present-day Iraq) around 2900 BCE was the trigger for the many flood stories that circulated in the ancient world, some already two thousand years old by the time King David came on the scene around 1000 BCE.

These ancient stories were attempts to explain why this happened, and the cause was fixed in divine wrath/retribution.

2. The story of Noah and the flood, though rooted in history, is also rooted in the stories told among other ancient people living in or near Mesopotamia. Israel’s version of the story is not the oldest one, and its existence certainly cannot be divorced from these older versions (like the Atrahasis epic and Gilgamesh epic).

Whether or not the author/s of the biblical version was/were aware of any of these older stories or consciously worked off of them is impossible to know and immaterial (though the similarities between the biblical account and the Atrahasis epic raises questions of dependence of the former on the latter, namely the sequence: creation—population growth—an unforeseen problem—devestating flood.)

Understanding the impact of these first two points will lead to the third:

3. The story does not depict an “accurate” account of history, but the ancient Israelites’ understanding of that long-past event that survived in cultural memory. Reading the flood story in Genesis does not tell us “what happened,” but it does tell us something of what the Israelites believed about their God.

In other words, it is a statement of theology, not history (despite the historical trigger mentioned above).

Just what that theology is isn’t laid out for us in black and white. You have to read between the lines a bit. But the story is certainly connected to two others in the Bible: creation and the exodus from Egypt.

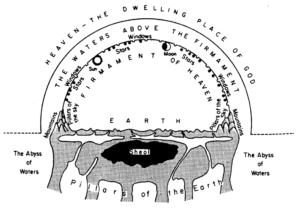

In the creation story (Genesis 1), God fixes a dome-like “firmament” to hold back the waters of chaos, which creates habitable space beneath, first the sky and then dry land. In the flood story, the “windows” of the firmament open up letting the waters of chaos crash back down onto the habitable space, thus returning the created order back into its original state of chaos.

space beneath, first the sky and then dry land. In the flood story, the “windows” of the firmament open up letting the waters of chaos crash back down onto the habitable space, thus returning the created order back into its original state of chaos.

The flood, as God’s retribution, is an undoing of creation which leads to a re-creation, as it were, with a new Adam: Noah.

The reason given in Genesis for this need to start over is human wickedness. Now, this raises (and has raised for a long time) all sorts of problems, namely why God goes so over-the-top. We’re only in the 6th chapter of the Bible. Couldn’t God think of another solution or was drowning the only option?

But this may be asking the wrong question. Rather than trying to explain why God would do such and such, it is more fruitful to ponder what this story tells us about Israel’s understanding of God.

The reason the gods flood the earth in the Atrahasis epic is because humans, who were created for slave labor, were making too much noise. The Israelites, on the other hand, had something else to say about the character of their God and the obligation of humanity to God as creatures created in God’s image.

They had a different theology.

The flood story also connects to the exodus story. In both stories, those not “on God’s side” drown (Noah’s “wicked generation” and the Egyptian army) when the waters held apart come crashing down.

Likewise, Noah and his family are saved in an “ark” waterproofed with pitch. The Hebrew word for ark is tevah (TAY-vah), and its only other use in the Bible is in the story of Moses, where, as an infant, he is placed in a “basket” (tevah) lined with pitch to escape Pharaoh’s edict to kill the Israelite male children. Both Noah and Moses are brought safely through a watery threat.

The flood story is not intended to be read in isolation. It is part of a big theological statement that spans Genesis and Exodus. That message can be put in different ways with different emphases, but here is my way:

Yahweh the creator is also Yahweh the deliverer. And when he delivers his people it is an act of creating them anew.

The creation of the people of God (first with Noah and then with the Israelites out of Egypt) was by the same means that God created the cosmos—by controlling water. The mighty God of creation is still present with Israel in her hour of need. The creator is the redeemer.

There’s a lot more to it than that—and we’ll leave to the side for now how this theme is continued elsewhere in the Bible, namely in the New Testament—for example, to be redeemed in Christ is to be a “new creation” for Paul (or a “new birth” for John).

This theology can be explored and played with, to be sure. But my only point is that reading the flood story as an ancient story packed with theology (in the context of other such ancient stories) is far more interesting and less stressful than fixating on and fretting over whether it happened—and building a life-size replica to try and prove it.

***I talk more about the interpretation of the Flood story in The Bible Tells Me So (HarperOne, 2014), Inspiration and Incarnation (Baker 2005/2015)***