I get asked all the time for advice about pursuing a PhD in Biblical Studies (or a related field). So here his what I think, in living color, and in no necessary order. (In years past, I’ve also posted related thoughts here, here, here, and here.)

here his what I think, in living color, and in no necessary order. (In years past, I’ve also posted related thoughts here, here, here, and here.)

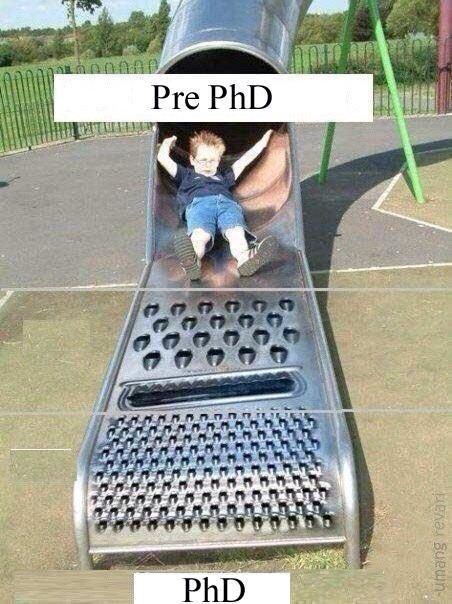

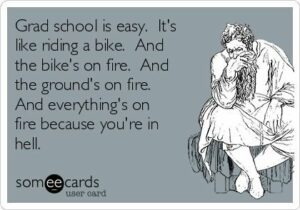

1. Only pursue the PhD if you absolutely love the thought of studying and writing for the next few years. And I mean love it. Really love it. If you are more,”I think it would be neat,” or “I’ve always wanted to try it,” don’t do it. You will be eaten alive.

2. Decide what your career goals are and what you are willing to settle for—because you likely will need to settle if your goal is what most have: a tenure track position. They are going the way of the dodo.

Have a Plan B and think of it as your Plan A.

3. The goal of the PhD is to work, and getting a job is as much about connections as anything. You increase your chances of employment if you are known as a friendly person who would make a great colleague. Super smart books worms with marginal social skills aren’t a hot commodity. Neither are smart nasty people.

4. Having said that, connections alone likely won’t do it. You won’t be competitive in the job market unless you get a PhD from a research university, and the higher the profile the better. Getting into such a school typically means an A average in relevant courses and no lower than an A- overall—plus finding three people to write recommendations and who are prepared to say you can walk on water.

5. A PhD program at an evangelical school will be easier to get into, but it will limit your job prospects. If, however, you are focused on teaching at a more conservative school, an evangelical PhD can help you, but even there evangelical schools like hiring graduates from research universities because it looks good in the catalog (nothing wrong with that).

6. In only the rarest of occasions will you be teaching your dissertation topic or even the bulk of the content that you covered in your PhD program. So during your time in school make yourself as marketable as possible by taking courses in (and/or being a teaching assistant in) diverse course offerings that will look good to prospective employers.

Actually, you might not even be teaching in a Bible or Theology department, but in a Religion or World Religions department. So really diversify your portfolio. That doesn’t mean taking classes in different types of ancient Greek or different eras of Mesopotamian history, but courses in topics that might sound like they belong in a Religion department—like anything in Judaism and Islam, and maybe Eastern religions.

7. Pastoring is a common default for PhDs in Biblical and related fields, which is a shame because churches deserve better—but if you go in with that goal in mind, it can work. Keep in mind, however, that a PhD in anything most definitely does not in and of itself qualify you to be a spiritual leader. Also, it is a rare church where you can actually use your learning rather than keep it hidden.

8. If you have a family—spouse and/or children—be sure to count the emotional and financial cost. If there are family expectations of private schools and really nice vacations, the money won’t be there unless it comes from another source (your spouse works, Oprah wants you for Super Soul Sunday). At some level, your family needs to buy in willingly to the adventure of graduate school. There’s enough pressure without the stress of unmet family expectations.

9. Especially if you come from an evangelical world, be prepared to have your boat rocked in graduate school. If you resist any transformation which comes from having your deepest assumptions challenged, you will be too busy practicing to be an apologist instead of a scholar. I know that sounds harsh because it is.

9. Especially if you come from an evangelical world, be prepared to have your boat rocked in graduate school. If you resist any transformation which comes from having your deepest assumptions challenged, you will be too busy practicing to be an apologist instead of a scholar. I know that sounds harsh because it is.

Create in your own mind an “expectation of change,” where you see yourself more on an adventure of discovery than simply being credentialed for the status quo.

Seek knowledge. Be bold. Come back and change the rest of us. Have some guts.

10. Work hard at remembering the doxological goal of your work. This can be difficult when the Bible and theology become a subject to analyze. Yet, analyze you must, and have at it. It’s great fun and very satisfying, even spiritually. But it is also deeply challenging—not simply the content per se (see 9) but the ease with which you can become detached from spiritual practices. You have to be as intentional about it as you are about your academic work.

Without giving too much advice here, let me suggest praying at least once in a while, where you do little of the talking [shock], and finding some community of faith somewhere where you are forced to interact with normal (non-academic) people who have real problems.